|

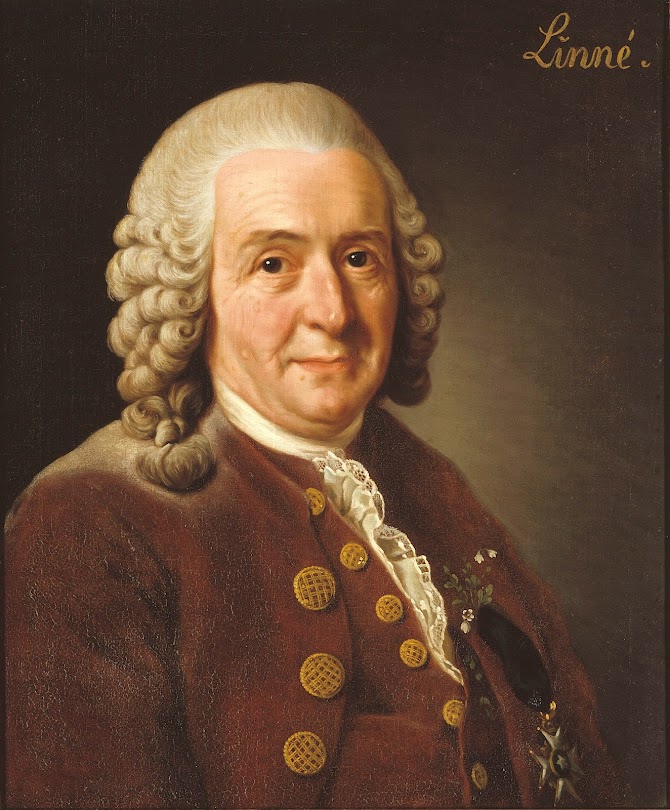

| Carl Linnaeus - aka: Carl von Linné |

|

| This plaque was been updated to include: "Linnaeus also applied this system to humans, without any scientific basis. He categorized humans based on race and assigned negative behavioral traits to Africans and other nonwhites. This system has been used to promote slavery and other racial injustices throughout history." |

A brief history of the Chicago Botanic Garden

The Chicago Botanic Garden traces its origins back to the Chicago Horticultural Society, founded in 1890. Using the motto "Urbs in Horto," meaning "city in a garden," the Society hosted nationally recognized flower and horticultural shows; its third was the World's Columbian Exposition Chrysanthemum Show, held in October of 1893 in conjunction with Chicago's World's Fair.

After a period of inactivity, the Chicago Horticultural Society was restarted in 1943. In 1962, its modern history began when the Society agreed to help create and manage a new public garden. With the groundbreaking for the Chicago Botanic Garden in 1965 and its opening in 1972, the Society created a permanent site on which to carry out its mission. The Garden today is an example of a successful public-private partnership. It is owned by the Forest Preserve District of Cook County, located in Glencoe and operated by the Chicago Horticultural Society.Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

[1] Carl Linnaeus also known after his ennoblement as Carl von Linné. Many of his writings were in Latin, and his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus (after 1761 Carolus a Linné).