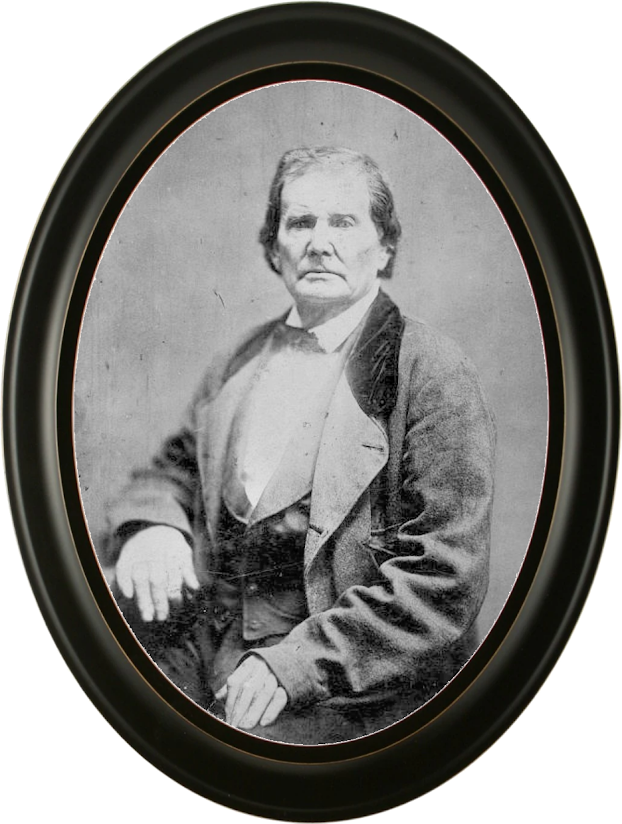

A list of the cabins that Thomas Lincoln, President Lincoln's father, occupied or built from his birth in 1778 until he died in 1851.

LINVILLE CREEK, VIRGINIA

Thomas Lincoln's father purchased two hundred and ten acres of land on Linville Creek, in Rockingham County, Virginia, on August 7, 1773. It's where he had been living since his marriage in 1770. Thomas Lincoln was born in 1778 in a cabin on that land tract. He lived there until 1782 when his parents migrated to Kentucky.

GREEN RIVER, KENTUCKY

The Lincolns lived on a tract of land in Lincoln County, now Casey County when they first arrived in Kentucky in 1782. It is more likely, however, that they resided in Crow's Station, near where Danville, Boyle County, now is, if they contemplated working the Green River lands. The ferocity of the Indians would not allow a scattered population at this time. Crow's Station was the headquarters of the pioneer, Lincoln, earlier in the year when he was on his prospecting trip in Kentucky.

LONG RUN, KENTUCKY

The first residence of the Lincolns, in Kentucky, of which we have positive evidence, is on Long Run, in Jefferson County. Here the family also found it necessary to live in the fort at Hughes Station when the Indians were troublesome, but likely they occupied the cabin on their 400-acre tract during part of the time. Thomas Lincoln's father, Abraham Lincoln, was killed by Native Americans in May 1786.

BEECH FORK, KENTUCKY

The exact site to which the Widow Lincoln moved her family after the massacre of her husband had yet to be determined, although the general location is made known by a road order which speaks of her cabin on Beech Fork. She reared her family and kept her home together until all the children, except Thomas, were married. Three weddings in the Lincoln home in 1801 were indirectly responsible for the family moving to Rardin County.

MARROWBONE CREEK, KENTUCKY

On November 28, 1801, Thomas Lincoln purchased a tract of land in Cumberland County, Kentucky. He undoubtedly put up a temporary structure to show possession and "batched" there long enough to claim the land grant. Evidence shows that his residence here was for short periods, as he was often found in Hardin County at various intervals.

MILL CREEK, KENTUCKY

The following purchase of Thomas Lincoln's was made to provide his mother with a home. In the fall of 1803, he paid £118 ($20,000US today) cash for a farm on Mill Creek, about twelve miles north· west of Elizabethtown in Hardin County. He divided his time between this and his Murrowbone Creek farm. His sister and her husband lived with his mother.

MIDDLE CREEK, KENTUCKY

Alter Thomas Lincoln married Nancy Hanks, in the Berry cabin, on Beech Fork. He brought his bride to Elizabethtown on Middle Creek in Hardin County, where he had purchased a lot and built a cabin. They lived for two years, and their first child was born here. The cabin's location has yet to be discovered, and the picture often exhibited as their Elizabethtown cabin home is spurious.

SOUTH FORK OF NOLIN, KENTUCKY

Thomas Lincoln moved from Elizabethtown to his new purchase on the South Fork of Nolin in late 1808. This farm was the largest tract of land he had owned, and he paid $200 cash for it. It was here on February 12, 1809, that Abraham Lincoln was born. The cabin was situated three miles south of where Hodgenville, LaRue county, now is, and in what was then Hardin county.

KNOB CREEK, KENTUCKY

About two years after Abraham Lincoln was born, his father moved the family to a cabin on Knob Creek and secured possession of a tract of land there. Abraham lived from when he was two years old until he was seven. This cabin site was also in what was then Hardin County but which later became LaRue County. It was the last Kentucky residence of the Lincolns.

LITTLE PIGEON CREEK, INDIANA

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas in 1816, Thomas Lincoln moved his family to what is now Spencer County, Indiana, and settled on the Southwest Quarter of Section 32, Township 4, South of Range 5 West. Tradition speaks of three different shellers which were erected on this site. Like other Lincoln cabins, the cabin which stood there at the time of the family's move mysteriously disappeared. This was the home of Abraham Lincoln from the time he was seven until he came of age.

SANGAMON RIVER, ILLINOIS

On March 14, 1830, the Lincoln caravan went into camp at Decatur, Macon County, Illinois. Ten miles southwest of this town, near the Sangamon River, the party's men erected a cabin with John Hanks's assistance. This cabin has been given so much prominence and furnished Information and brochures about its being exhibited on Boston Common. Pieces of the cabin were sold for souvenirs. Tradition states that what was left of it was lost at sea en route to England.

BUCK GROVE, ILLINOIS

Sickness, the rigors of a cold winter, and the possibility of Abraham leaving home were responsible for Lincolns Starting back towards Indiana after a year's residence on the Sangamon. They were persuaded to settle in Buck Grove, close to some of Mrs. Lincoln's relatives, where a cabin was erected in Section 5, Township 11, Range 8. Lincoln remained here on this first Coles County site for three years.

WALKER'S PLACE, ILLINOIS

There is evidence that Lincoln moved from section five to section ten after his Buck Grove residence and purchased forty acres of land on which he built a cabin. This home was about three-quarters of a mile south of where the town of Lema, Coles County, now stands.

PLUMMER'S PLACE, ILLINOIS

On November 25, 1834, Thomas Lincoln purchased 80 acres of land in the same township where he was residing, securing half of the quarter section number sixteen. A cabin was erected, and a residence was established until the sale of the property on December 27, 1897. This was probably the third cabin Thomas Lincoln had erected in Coles County.

GROVE NEST PRAIRIE, ILLINOIS

By the spring of 1838, Thomas Lincoln had become established in the cabin on the new purchase at Goose Nest Prairie, also in Coles County. Here he lived until the day he died in 1851. The place where he died finally came into possession of the National War Museum company, but, like some of the former homes of the pioneer, its disappearance is clothed in obscurity.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.