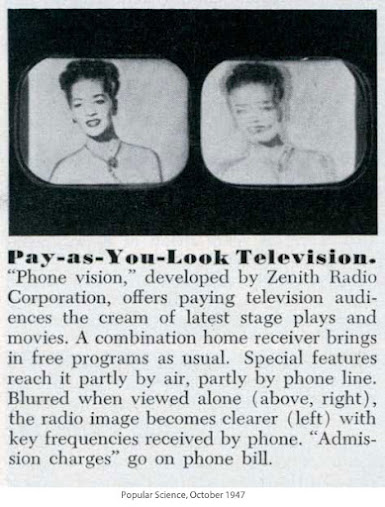

Phonevision was a project by Zenith Radio Company to create the world's first pay television system. It was developed and first launched in Chicago.

E.F. McDonald's vision wasn't that far from what some early pioneers intended for radio. Though he continued to call himself "the father of the radio," Dr. Lee de Forest (inventor of the "audion" vacuum tube and the "discoverer" of regeneration if the courts are to be believed) turned his back on the broadcast frenzy. He was appalled by the crass commercialism already in place by the 1930s. De Forest thought that the public should be allowed to sit down and enjoy a concert, a history lesson, or just simply the news of the day without being huckstered by a fast-talking shaving cream salesman.

But it was not to be. It all boiled down to economics and time. Radio needed commercial sponsorship if it was to survive and grow. As the industry was abandoning the mechanical era and embracing the new electronic era of television research, design and manufacture, it became abundantly clear that if television was to survive and surpass radio as the popular medium, it needed the cash flow that only commercial television sponsorship could provide. McDonald, chairman and owner of independent radio manufacturer Zenith Radio Corporation in Chicago, firmly believed De Forest's thinking. Zenith had experimented with "subscription television" as early as 1931.

By 1947 they had a working system and, in 1951, coined and trademarked the name "Phonevision" to identify their efforts. After receiving FCC approval, a 90-day test run was conducted utilizing 300 families from the Lakeview-Lincoln Park Chicago area. This area was chosen due to the limited broadcast range of the station.

KS2XBS was located at the Field Building downtown, and its Phonevision central distribution center was at 3477 North Clark Street. The lucky 300, equipped with a set-top converter (the first in a long line of boxes to sit atop the TV) and a dedicated telephone line, enjoyed first-run movies that were supplied under a special deal with Zenith and some of the major film studios. A typical broadcast day for Phonevision subscribers might include The Enchanted Cottage, a Robert Young film from 1945 (very recent compared to the movies available on television at the time). The film would be shown three days in a row, scheduled at different times each day. The station would receive the movie two days in advance and store them in a special film vault. Jerry Daly, along with his projectionist staff of Jim Starbuck and Roland Long, was responsible for the safety of the film. Television, in the beginning, was considered Hollywood's mortal enemy. But McDonald and Zenith were determined to prove that the two could work side by side. For the not-so-low price of $1 ($3.25 in 1951), folks could see a major motion picture in their living rooms without commercial interruption.

The experiment was attracting citywide attention. People tried to build or buy pirate boxes to circumvent the system and avoid payment. In the first month of the test, only the video was scrambled. The audio was as clear as a whistle; many sat through the scrambled picture and just listened. The second month, however, changed all that when Zenith began to scramble the sound, making all those pirate boxes obsolete.

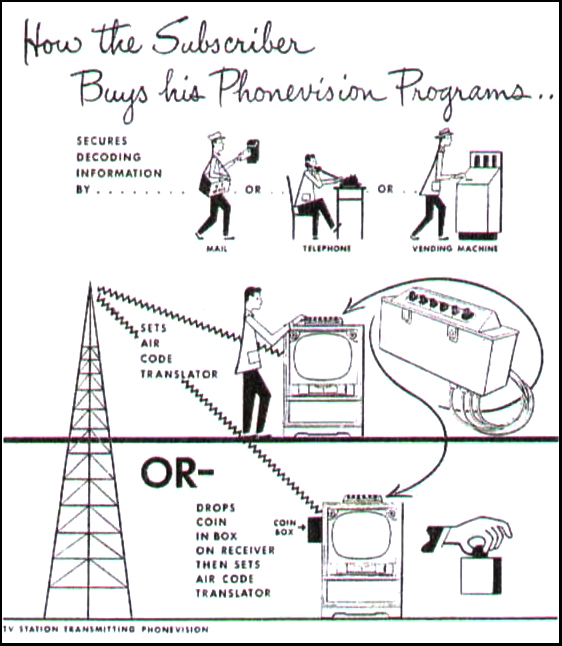

The people who paid for their Phonevision service were required to do the following to watch their movies. Call the Phonevision operator and ask to be "plugged in." Daisy Davis and Dean Barnell supervised the operators day and night. The subscriber would turn to channel 3 on the television and turn on his Phonevision converter, which would be patched into the antenna terminals on the set and a phone line. According to The Zenith Story, an in-house 1954 publication, those families averaged about 1.73 movies weekly. Not quite enough to qualify as a commercial success. The results were disappointing as McDonald had hoped to transform KS2XBS into commercial licensed WTZR.

The experiment was plagued by technical problems right from the beginning. Passing planes and trucks was known to wreak havoc on the signal making the experience less than enjoyable. This was, of course, provided you even received the scrambled signal. But Zenith refused to give up and, in 1953, was ready to try again.

But by this time, commercial television was firmly in place, and the advertisers (who told the networks when to jump) generally frowned upon the "alternative" to commercially sponsored television. Educational television, though noncommercial, was not considered a threat. By 1953, all of the experimental licenses in Chicago had been replaced by commercial ones. Zenith, so involved with its Phonevision system, apparently didn't see or chose to ignore the situation, and KS2XBS found itself in a difficult situation.

1953 was the year that brought together The American Broadcasting Company and United Paramount Theaters. Because licensees could only own one television station in the same market- a problem quickly arose. UPT, through its Balaban & Katz subsidiary, owned WBKB Channel 4. ABC-TV owned and operated WENR-TV on channel 7. CBS, itself lagging behind for a completely different reason- its Peter Goldmark-designed field sequential color television system, did not own a station in the Chicago market. Its shows were carried mainly by WBKB. CBS quickly coughed up $6 million for the station in a sweetheart deal arranged by CBS head Bill Paley and ABC head Edward Noble.

sidebar

Subscription broadcast television used a method referred to as "narrowcasting." Employing this method, a station would transmit a scrambled picture and a code encoded in a single sideband of the audio signal. A set-top decoder would read the code and descramble the picture. Different "levels" of service (in reality, differing codes) would allow the subscriber access to the service's regular programming, special events, and late-night adult programming.

But the sale was not without its conditions. For several years, Milwaukee's WTMJ-TV and KCZO, a Kalamazoo station, had been broadcasting on channel 3, and this caused interference problems for both stations. The FCC ordered WTMJ-TV to move to channel 4 and WBBM-TV to channel 2.

McDonald cried foul and petitioned the FCC to allow Zenith to continue its experiments on channel 2 since "they had occupied the channel since 1939" when W9XZV, Zenith's original station on channel 1, first went on air on March 30, 1939. A shuffling of VHF allocations found the station at the number two position. But there are no squatters' rights in broadcasting. Whether it was because of the deep pockets at CBS or just the FCC's disappointment with Zenith's less-than-desirable results of its Phonevision experiments, the commission stood firm. It was the second time Zenith's channel position was challenged. Before the war, NBC had threatened to petition the FCC for the W9XZV channel 1 license. On July 5, 1953, WBBM-TV moved to its current home on channel 2, and Zenith signed off for good.

Oddity Archive: Episode 89 – Prehistoric Pay-Per-View

The 50-second show's opening will test your memory and prove your age.

This wasn't the end of Phonevision, however. Zenith conducted another experiment with an improved system that would have been tried on KS2XBS. In 1954, Zenith used New York station WOR-TV, and this experiment was considered a success over the Chicago version. In the same year, Zenith also tried its Phonevision system in New Zealand and Australia. By the early seventies, Zenith was still trying to make its Phonevision a successful commercially viable venture, this time in Hartford, Connecticut, and again as late as 1986 using the Centel Cable system in Traverse City, Michigan. None were successful enough.

The idea of a pay television system in Chicago lingered in obscurity until the early eighties when the changing face of broadcast television inspired one major network to re-examine an old idea.

It was not until 1983 that Chicago saw another pay television experiment. This time ABC would use its WLS-TV to try a strategy to increase competition between cable television and home video.

In Chicago, viewers were offered three choices in subscription television: a service called Sportsvision, which had been formed by a partnership between White Sox owners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn and media mogul Fred Eychaner, who, through a series of intricate deals, brought WPWR channel 60 to the Chicago airwaves and split the license with Marcello Miyares who ran WBBS; ON-TV, a service of Oak Communications Inc., which purchased forty-nine percent of struggling UHF outlet WSNS channel 44 to air its content on that station as well as others in large metropolitan areas across the country; and Spectrum, a division of United Cable, that purchased airtime from WFBN channel 66, which was actually licensed to Joliet.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ is RATED PG-13. Please comment accordingly. Advertisements, spammers and scammers will be removed.