A single event, happenstance or circumstance can define who you are and how you'll be remembered, good, bad, or vile.

|

| Thomas H. "Boston "Corbett |

Thomas H. "Boston "Corbett shall forever be known as the Union soldier who avenged President Abraham Lincoln's death by killing John Wilkes Booth, but his fascinating story hardly ends there.

Born in England in 1832, Corbett migrated to New England with his family before the Civil War. Tragically, he lost his wife and daughter in childbirth. Depressed, Corbett started drinking. Later, he stumbled into a revival meeting and got sober. Corbett changed his given name to "Boston," the city where he was baptized.

Corbett was forced to surrender twice during the civil war. The second time he was sent to Andersonville (aka Camp Sumter) Confederate prison camp in Georgia. He attempted to escape at least once. After five brutal months at Camp Sumter, Corbett was released in an exchange in November 1864. He was admitted to the Army hospital in Annapolis, Maryland, where he was treated for scurvy, malnutrition, and exposure.

Corbett rejoined the 16th New York Cavalry near the end of the war. On his return to his company, he was promoted to sergeant. Only two out of fourteen men from his unit survived captivity.

Of the approximately 45,000 Union prisoners held at Camp Sumter during the civil war, nearly 13,000 died (29%). The chief causes of death were scurvy, malnutrition, diarrhea, and dysentery.

Corbett volunteered to go after John Wilkes Booth following Lincoln's assassination in 1865.

The Pursuit of John Wilkes Booth

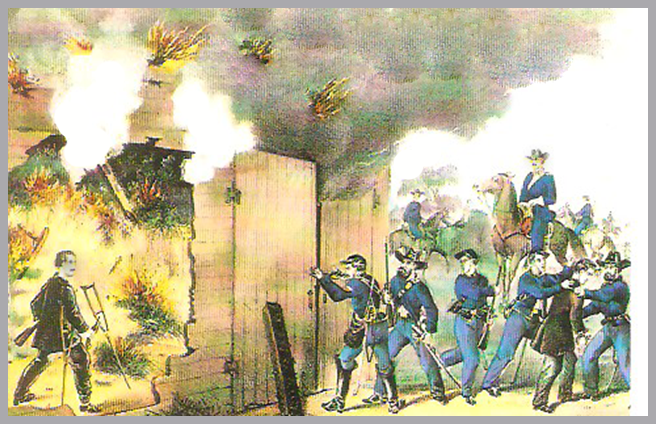

On April 24, 1865, Corbett's regiment was sent to apprehend John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, whom Booth fatally shot on April 14, 1865. On April 26, the regiment surrounded Booth and one of his accomplices, David Herold, in a tobacco barn on the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett.

Herold surrendered, but Booth refused and cried out, "I will not be taken alive!". The barn was set on fire to force him into the open, but Booth remained inside. Corbett was positioned near a large crack in the barn wall.

Shooting Booth

In an 1878 interview, Corbett claimed that he saw Booth aim his carbine, prompting him to shoot Booth with his Colt revolver despite Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton's orders that Booth is captured alive. The bullet struck Booth in the back of the head behind his left ear, passed through his neck, and exited somewhere in the barn. A low scream of pain like that produced by a sudden throttling came from the assassin, and he pitched headlong to the floor. Corbett and the other soldiers would note a sense of poetic, or cosmic, justice in that Lincoln and Booth were each shot around the same area of the head. And the damage to Booth was no less severe than that to Lincoln: the bullet had pierced three vertebrae and partially severed his spinal cord, paralyzing him. Their conditions were different as well. As Mary Clemmer Ames summed it up, "The balls entered the skull of each at nearly the same spot, but the minor difference made an immeasurable difference in the sufferings of the two. Lincoln was unconscious of all pain, while his assassin suffered as exquisite agony as if he had been broken on a wheel."

The Death of Booth

Booth asked for water in a weak voice, and Lt. Colonel Everton Conger and Colonel Lafayette C. Baker gave it to him. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he immediately spat out, unable to swallow. The bullet wound prevented him from swallowing any of the liquid. Booth asked them to roll him over and turn him facedown, and Conger thought it was a bad idea. Then at least turn me on my side, the assassin pleaded. They did, but Conger saw that the move did not relieve Booth's suffering. Baker noticed it, too: "He seemed to suffer extreme pain whenever he was moved...and would repeat several times, "Kill me."

At sunrise, Booth remained in agonizing pain. His pulse weakened as his breathing became more labored and irregular. In agony, unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered as he gazed at them, "Useless . . . Useless." These were his last words. A few minutes later, Booth began gasping for air as his throat continued to swell, then there was a shiver and a gurgle, and his body shuddered before Booth died from asphyxia. He died two hours after Corbett shot him.

Mr. Boston Corbett

|

| Colorized |

Conger initially thought Booth had shot himself. After realizing Booth had been shot by someone else, Conger and Lt. Doherty asked which officer had shot Booth. Corbett stepped forward and admitted he was the shooter. When asked why he had violated orders, Corbett replied, "Providence directed me."

Court-martial

He was immediately arrested and accompanied by Lt. Doherty to the War Department in Washington, D.C., to be court-martialed. When questioned by Secretary Edwin Stanton about Booth's capture and shooting, both Doherty and Corbett himself agreed that Corbett had, in fact, disobeyed orders not to shoot. However, Corbett maintained that he believed Booth had intended to shoot his way out of the barn and that he acted in self-defense. He told Stanton, "...Booth would have killed me if I had not shot first. I think I did right." Corbett maintained that he didn't intend to kill Booth but merely wanted to inflict a disabling wound, but either his aim slipped or Booth moved when Corbett pulled the trigger. Stanton paused and then stated, "The rebel is dead. The patriot lives; he has spared the country expense, continued excitement, and trouble. Discharge the patriot." Upon leaving the War Department, Corbett was greeted by a cheering crowd. As he made his way to Mathew Brady's studio to have his official portrait taken, the crowd followed him asking for autographs and requesting that he tell them about shooting Booth. Corbett told the crowd:

I aimed at his body. I did not want to kill him . . . I think he stooped to pick up something just as I fired. That may probably account for his receiving the ball in the head. When the assassin lay at my feet, a wounded man, and I saw the bullet had taken effect about an inch back of the ear, and I remembered that Mr. Lincoln was wounded about the same part of the head, I said: "What a God we have... God avenged Abraham Lincoln."

Contradictions

Eyewitnesses to Booth's shooting contradicted Corbett's version of events and expressed doubts that Corbett was responsible for shooting Booth. Officers near Corbett at the time claimed that they never saw him fire his gun (Corbett's gun was never inspected and was eventually lost). They contended that Corbett came forward only after Lt. Colonel Conger asked who had shot Booth. Richard Garrett, the farm owner on which Booth was found, and his 12-year-old son Robert contradicted Corbett's testimony that he acted in self-defense, and both maintained that Booth had never reached for his gun.

While there was some criticism of Corbett's actions, he was primarily considered a hero by the public and the press. One newspaper editor declared that Corbett would "live as one of the World's great avengers." For his part in Booth's capture, Corbett received a portion of the $100,000 ($1.7 million today) reward money, amounting to $1,653.84 ($28,300 today). His annual salary as a U.S. sergeant was $204 ($3,500 today). Corbett received offers to purchase the gun he used to shoot Booth, and he refused, stating, "That is not mine—it belongs to the Government, and I would not sell it for any price." Corbett also declined an offer for one of Booth's pistols as he did not want a reminder of shooting Booth.

After shooting Booth in a Virginia tobacco barn, Corbett became somewhat famous, but he was plagued by paranoia and irrational anger. A Milliner [1] before the war used mercury to cure felt hats, slowly making him "mad as a hatter," from what we know today as mercury poisoning.

As a result, Corbett was committed to the Topeka Asylum for the Insane in 1887.

Sometime in 1887, Corbett stole a horse tethered to a post and escaped. He told a friend he met at Camp Sumter that he was going to Mexico.

Boston Corbett simply disappeared and was never seen or heard from again.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Contributor: Ford's Theatre National Historic Site.

Contributor: Lincoln Lore

[1] A Milliner is a person who is involved in the design, manufacture, sale, or repair of hats. A Haberdasher (British term) is a dealer in Notions (the equivalent English term), ribbons, buttons, snaps, thread, needles, and similar sewing goods.