When Illinois entered the Union in 1818, its constitution, like those of the other 20 states, expressly gave the vote only to "white, male inhabitants above the age of twenty-one years." Illinois' second constitution, adopted in 1848, allowed men to vote for a greater number of officials than previously, but it still excluded women from using the ballot. The state's first documented speech in favor of women's suffrage was made by Mr. A.J. Grover, editor of the Earlville Transcript. His talk inspired Mrs. Susan Hoxie Richardson (a cousin of Susan B. Anthony) to organize Illinois' first woman suffrage society. Another transplant to LaSalle County who supported the suffrage cause at the same time was Prudence Crandall. A school teacher in Mendota, she had been forced to flee Connecticut because she taught Negro girls in her school. Crandall worked in Illinois as an early advocate of the enfranchisement of both black and white women.

|

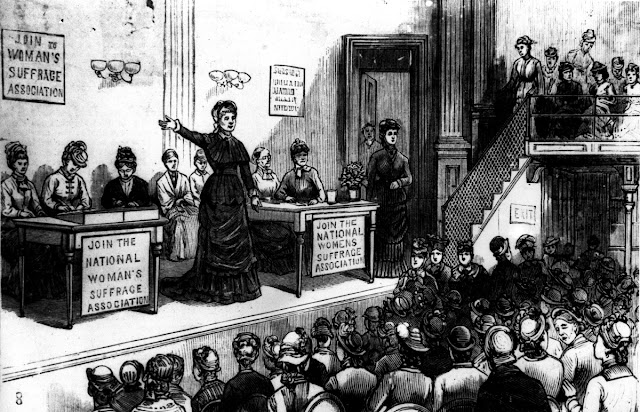

| The First Illinois Woman Suffrage Convention was held in Chicago in 1869. |

In 1869, Livermore organized an Illinois woman suffrage convention, while at the same time one was being held a block away by "Sorosis," another newly formed woman's organization. The Chicago Tribune reported that women obviously didn't have the capacity to govern since they couldn't even agree on planning a common convention. The paper predicted that "The public will now be annoyed for six months by the characteristic ill humor of a lot of old hens trying to hatch out their addled productions." While admitting that Livermore's group was intelligent and business-like, the Chicago Times sarcastically stated that the appearance of the Sorosis convention "was the best argument for woman suffrage, the men being ladylike and effeminate, the women gentlemanly and masculine."

The Livermore faction, full of distinguished clergymen and educators and hearing addresses from both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, organized themselves into the Illinois Woman Suffrage Association and elected Livermore President. Within a month, she created the Agitator, a suffrage newspaper, and by September, she had established local associations in Aurora, Plano, Yorkville, and Sandwich. However, later that year, the Agitator was merged with the Woman's Journal, published in Boston, and in 1870, Livermore and her Universalist minister husband moved to Massachusetts, where she continued to work for social reform and women's issues until her death in 1905.

Because another state constitutional convention could not legally be called in Illinois for twenty years, members of the women's suffrage movement began a push for changes in individual laws. While universal suffrage was set back, gains in specific women's rights were accomplished. Through the efforts of Alta Hulett, Myra Colby Bradwell, her husband Judge James Bradwell, and others, laws passed between 1860 and 1890 included women's right to control their own earnings, to equal guardianship of children after divorce, to control and maintain the property, to share in a deceased husband's estate, and to enter into any occupation or profession. This included becoming an attorney (Hulett was the first woman admitted to the Illinois bar) even though women could not legally sit on Illinois juries until 1939 (based on a bill sponsored by Lottie Holman O'Neill, Illinois' first woman state representative).

In 1873, Judge Bradwell secured the passage of a statute that allowed any woman, "married or single, " who possessed the qualification required of men to be eligible for any school office in Illinois created by law and not the constitution. Even though they couldn't vote for themselves, in November 1874, ten women were elected as County Superintendents of Schools.

Probably the two most important people in the Illinois suffrage movement during this time were Elizabeth Boynton Harbert and Frances E. Willard. Harbert helped keep the Illinois association alive by serving as president for a total of twelve years.

She was a prolific writer as well as the founder and first president of the Evanston Women's Club. Her early writings stated that both women and society were injured by pushing children into stereotypical sex roles that confined females to the "women's sphere." She thought that this practice condemned a woman to a non-productive lifetime of dependence on others.

However, Harbert's later writings admit that perhaps women did have some virtues and traits that were typically characteristic of her sex, such as purity, charity, and fidelity. She wrote that women were "born to soothe and to solace, to help and to heal the sick world that leans upon her." Therefore, giving women the vote would allow them to fulfill their natural nurturing function. In essence, Harbert's writings exemplified the whole movement's shift from an elite intellectual pursuit for justice to a middle-class reform movement that would benefit society.

Illinois' most famous reformer of this period was undoubtedly Frances Willard. After her first experiences with the Illinois legislature, Miss Willard returned to Evanston, where she served as President of the College for Ladies and later Dean of Women at Northwestern University. In 1874, she resigned from her position and became totally immersed in the temperance movement that swept the country. She helped establish the anti-liquor Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and eventually served as president of the Chicago, state, and national organizations. She became a believer that giving women the sacred ballot was the only way to get rid of the demon spirits that were ruining the American family.

On March 24, 1877, seventy women of the Illinois WCTU presented the General Assembly in Springfield a petition signed by 7,000 persons asking that no licenses to sell liquor be granted that was not asked for by a majority of citizens of location. Failing their efforts to influence the legislature, they returned in 1879. They presented petitions signed by 180,000 who favored what was termed the "Home Protection" bill, a proposed law that would put liquor sales under local control and allow women to vote in these referenda. Although the bill eventually was defeated, on March 6 of that session, Frances Willard became the first woman ever to stand at the speaker's podium and address an official session of the Illinois General Assembly.

Despite these defeats, the suffrage and temperance movements kept coming back every two years in an effort to obtain some form of female franchise. In 1891, the Illinois legislature was informed by a petition from Jackson County women that they and the "vast majority" of Illinois women did not want the vote. Since ''they belonged to that class of women who kept their own homes and took care of their own children," they were perfectly content to let their fathers, husbands, and sons vote for them. However, other petitioners agreed with the women citizens of Pittsfield who demanded "the right and privilege of voting in municipal elections "as a means to better government and that we may no longer be subject to the control of besotted men and the vicious classes."

Illinois women finally received limited franchise rights on June 19, 1891, when the state legislature passed a bill that entitled women to vote at any election held to elect school officials. Since these elections were often held at the same time and place as elections for other offices, women had to use separate ballots and separate ballot boxes. Subsequent Illinois Supreme Court cases also allowed women to serve as and cast ballots for the University of Illinois Trustees. This resulted in Lucy Flower becoming the first woman in Illinois to be elected by voters state-wide in 1894.

A little-known side-light in the history of Illinois suffrage is the story of Ellen Martin of Lombard. Many Illinois towns had special charters of incorporation written into law just before the 1870 state constitution forbade "privacy laws." While these charters specifically gave the vote only to males, Lombard's copy (perhaps unknowingly) stated that "all citizens" above the age of 21 who were residents shall be entitled to vote in municipal elections. Accordingly, Martin, "wearing two sets of spectacles and a gripsack," went to her polling place with a large law book and fourteen other prominent female citizens. When they demanded their right to vote, allegedly, the judges were so flabbergasted that one was taken with a spasm and another "fell backward into the flour barrel." The judges, however, eventually ruled in her favor, and the first 15 female votes in Illinois were tabulated on April 6, 1891.

Another Lady Lawyer who kept the suffrage movement fueled in its darkest days was Catharine Waugh McCulloch. In 1890, she became the legislative superintendent of the renamed Illinois Equal Suffrage Association. For the next twenty years, she kept the pressure on the General Assembly to approve a law that would allow women to vote in municipal and presidential elections. However, she constantly faced opposition from both individuals and organized groups.

One apparently frustrated man wrote the Illinois Senate expounding on his view that all suffragists secretly hate men and that giving them the vote would ruin the family. Women were, he wrote, "the sex which has accomplished absolutely nothing, except being the passive and often unwilling and hostile instruments by which humanity is created." During this era of labor unrest and mass immigration, a representative of the "Man Suffrage Association" wrote to his Illinois Senator and claimed that every socialist, anarchist, and Bolshevist was for woman suffrage.

Representing the distaff side of the anti-forces was Chicago homemaker Caroline Fairfield Corbin, who founded the Illinois Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women in 1897. She believed that women should stay in their "sphere" of home life and allow their husbands and fathers to legislate for their protection. She viewed women's sufferage akin to socialism and fought both movements with religious zeal. Every time the suffragists tried to advance, she and her organization tried to push them back, arguing that most women were opposed to obtaining the vote.

After 20 years of fruitless petitioning to change the state's laws, the Illinois association began to change their tactics and allies. After 1900, more and more women's clubs and labor organizations endorsed some form of woman suffrage legislation. Between 1902 and 1906, the Illinois Federation of Women's Clubs endorsed several municipal suffrage bills, including one that exempted women who couldn't vote from paying taxes.

Beginning in July 1910, McCulloch, Grace Wilbur Trout, and others began making automobile tours around the state. A special section of the July 10th edition of the Chicago Tribune detailed the plan of four women speakers, accompanied by two reporters, to visit 16 towns in 7 northern Illinois counties in 5 days. Chicagoan Trout was supposed to give the opening address and make the introductions. The other women were to speak about the legal aspects, laboring women's viewpoint, and the international situation regarding suffrage. Reflecting the tension that often existed between different factions, McCulloch later criticized Trout for speaking much too long and dominating the tour.

|

| Grace Wilbur Trout, President of the Chicago Political Equality League. |

The Alpha Suffrage Club is believed to be the first Negro women's suffrage association in the United States. It began in Chicago, Illinois, in 1913 under the initiative of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her white colleague, Belle Squire.

Read the first Alpha Suffrage Club's newsletter here:

The Alpha Suffrage Record; Volume 1, Number 1, March 18, 1914

During the 1913 session of the General Assembly, a bill was again introduced giving women the vote for Presidential electors and some local officials. With the help of the first-term Speaker of the House, Democrat William McKinley, the bill was given to a favorable committee. McKinley told Trout he would only bring it up for a final vote if he could be convinced there was sentiment for the bill in the state. Trout opened the floodgates of her network, and while in Chicago over the weekend, McKinley received a phone call every 15 minutes day and night. On returning to Springfield, he found a deluge of telegrams and letters from around the state, all in favor of suffrage. By acting quietly and quickly, Trout had caught the opposition off guard.

|

| The Rainy Day Suffrage Parade passes by the Chicago Public Library during the 1916 Republication National Convention. |

Women in Illinois could now vote for Presidential electors and for all local offices not specifically named in the Illinois Constitution. However, they still could not cast a vote for state representatives, congressmen, or governors; and they still had to use separate ballots and ballot boxes. But by virtue of this law, Illinois had become the first state east of the Mississippi to grant women the right to vote for President. National suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt wrote:

"The effect of this victory upon the nation was astounding. When the first Illinois election took place in April, (1914) the press carried the headlines that 250,000 women had voted in Chicago. Illinois, with its large electoral vote of 29, proved the turning point beyond which politicians at last got a clear view of the fact that women were gaining genuine political power."

|

| On June 26, 1913, Governor Edward F. Dunne, seated of Illinois, signed the Suffrage Bill that gave Illinois women the right to vote. Governor Dunne signed the bill in the presence of his wife, left, and suffragette leaders Grace Wilbur Trout, Elizabeth Booth, female lawyer Antoinette Funk, and teachers union leader Margaret Haley, seated. |

In June 1916, many Illinois women were among the 5,000 who marched in Chicago to the Republican National Convention hall in a tremendous rainstorm. Their efforts convinced the convention to include a Woman's Suffrage plank in the party platform. They got Presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes to endorse the proposed constitutional amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Three years later, Congress finally passed Susan B. Anthony Amendment. First introduced in Congress in 1878, it stated simply:

"The right of citizens of the

United States to vote shall not be

denied or abridged by the United States

or by any State on account of sex."

National President Carrie Chapman Catt proposed the idea of a "League of Women Voters" as a memorial to the departed leaders of the Suffrage cause. The next year, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was disbanded, and the League of Women Voters was founded on February 14 at the Pick Congress Hotel in Chicago. Present at the creation were suffragists Jane Addams, Louise de Koven Bowen, Agnes Nestor, Wells-Barnett, Haley, McCulloch, and Trout. Gone but not forgotten were the women who first led the way: Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Frances Willard, and countless others.

On November 15, 1995, a simple plaque was dedicated in recognition of their efforts in the Illinois State Capitol next to the statue of Lottie Holman O'Neill of Downer's Grove; the first woman elected to the Illinois General Assembly.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ is RATED PG-13. Please comment accordingly. Advertisements, spammers and scammers will be removed.