The Paleoindian time period covers the years 11,000 to 8,000 BC or the Ice Age.

The Archaic period stretches from 8,000 to 1,000 BC.

The Woodland period from 1,000 BC. to 1,000 AD.

The Mississippian period from 800 to 1550 AD.

There is no truth to the myth of Indians jabbing mammoths and mastodons with spears. Instead, Indians likely used what was called an atlatl, which was designed to increase speed and force when throwing a spear from a distance. As evidence, archaeologists have found spear points embedded in bone with massive impact tracts.

|

| Hunting with an atlatl. |

While there are no works in Illinois so elaborate in construction as the prehistoric Cahokia Mounds city, there are other sites in America that have been given the names of "Fort Ancient" on the Maumee in Ohio, "Fort Azatlan" on the Wabash in Indiana, and "Fort Aztalan" on Rock River in Southern Wisconsin. There is a number whose form of construction shows that they must have been intended for warlike purposes and that they were formidable of their kind and for the period in which they were constructed.

Closely related in interest to the works of the mound-builders in Illinois probably, owe their origin to another era and an entirely different race.

Old Stone-Lined Graves Found at Cahokia Mounds' Monks Mound in 1914

T.T. Ramey, of Edwardsville, one of the owners of Monk's Mound, southwest of Edwardsville, recently told for the first time of the most perfect grave which has been opened in the vicinity. Monk's Mound is the center of a group of a hundred smaller mounds, and is believed to have once been the home or place of worship of a race which passed from existence and left no records.

Unlike all other graves, the tomb was entirely lined with flagstones from 1 to 4 inches thick. This disproves the theory that the race was unfamiliar with stone cutting. The discovery caused curiosity to open a small mound west of the big one. The grave was only 3 feet deep. It was 20 inches wide and 6 feet long, and from all indications three or possibly four bodies were buried. In opening the grave it was carefully studied. The bodies were buried exactly north and south, the same position of the oblong mounds.

This discovery has considerable importance from a chronological point of view. Of the Indian tribes occupying the American Bottom in primitive times, the two longest in possession of that region are vaguely known to us by the relics of their arts and customs occasionally found, or still conspicuous, there. The one were the people who built the great mounds in that locality that have so long excited the wonder and interest of antiquarians; and the other, not in the category of mound builders, distinguished by the peculiar mode of burying their dead in stone-lined cists (an ancient coffin or burial chamber made from stone or a hollowed out tree). While both were essentially Indians of the same generic type, advancing in culture by slow stages to a higher state, it is certain they differed broadly in many characteristics and methods of life.

They were both semi-sedentary residents there for long periods, depending for subsistence more upon the products of agriculture than of the hunt. In their stone implements, pottery and domestic utensils of equal artistic and mechanical excellence there are well marked features of dissimilarity, and craniologists have noted a difference in the general conformation of their skulls. But to us the most convincing evidence of their separate identity is seen in the manner of disposing of their dead by the one tribe, and the absence of that mortuary custom by the other. Those burying their dead in the ground in stone-lined graves have been named by archeologists the “Stone Grave Indians.”

Their populous and long established home was in the valleys of the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers, where their extensive cemeteries, containing thousands of stone-lined cists, have been discovered and explored.

Stone-Lined Grave - Indian Burial.

They were not "familiar with cutting of rock," and had not discovered the use of metals, or attained instruments of any kind capable of cutting rock. They employed for the lining and covering of their graves the thin aluminiferous flagstones, in their natural state, found in abundance in various localities. The only tool mark discernible on those flagstones was that of the stone hammer. Yet, many of them, shaped by that means, were so neatly fitted and adjusted together as to present the appearance of having been cut, or ground, to conform to each other. Many of the graves were paved on the bottom with large mussel shells, or potsherds, and in many the sides and ends were skillfully lined with closely-fitted fragments of large pottery vessels. Each one was covered with rough broad flag stones.

Tracing the migrations of their colonies by their tribal custom of inhumation, it is known that large bands of them, emerging from middle Tennessee, crossed the Ohio into southern Indiana; then moving westward into southern Illinois, abided for a long time about the Saline Springs there, and mined vast areas of the chert beds (a hard and compact sedimentary rock) in Alexander and Union counties. Following the Mississippi northward, they settled in the central part of the American Bottom, where numerous clusters of their stone-lined graves attest quite a protracted period of undisturbed occupancy. From there they passed westward beyond the Mississippi.

The builders of the huge earthworks in the American Bottom were Indians of other ethnic derivation, with widely different customs, and perhaps ranking higher in the scale of progress towards civilization. In what manner they disposed of their dead is still unknown. No cemeteries, and very few isolated graves certainly identified as theirs, have yet been discovered. Their custom in this respect may have been that of certain other North America Indians, in periodically gathering from the prairie and tree scaffolds, the desiccated bodies of their deceased kinsmen, and cremating them with barbaric ceremonies. Possibly future exploration of the smaller mounds in the Cahokia district may yet solve the problem of their mortuary usages. With the knowledge we have of Indian life, it is not to be supposed that the tenancy of that splendid territory by the two early tribes mentioned was contemporaneous; and, with the limited reliable data available, the question of priority in possession has always been one difficult to determine. Upon this point the discovery of that stone-lined grave is valuable and almost conclusive. The description of the grave by Mr. Ramey leaves no room to doubt that it was made there by the only tribe of prehistoric times in the Mississippi basin that invariably buried their dead in that way, and in consequence designated the “Stone Grave Indians.” Solitary graves of that kind sometimes groups of two or three of them have been found scattered over the country as far north as the Sangamon River, presumably grim mementos of casualties among those people during hunting expeditions. The fact that this cist, but three feet deep, was in the surface of an artificial mound proves it to have been an intrusive burial of much later date than the mound itself, and, inferentially, made there after all the mounds had been abandoned; which gives strong support to the view that the Stone Grave immigrants did not arrive in the American Bottom until long after the builders of the great temple mounds there had run their course and disappeared.

DR. J. F. SNYDER

Virginia, Illinois

Virginia, Illinois

January 1914

Are those works which bear evidence of having been constructed for purposes of defense at some period anterior to the arrival of white men in the country?

The prehistoric Cahokia Mounds Stockade was located in modern-day Collinsville, Illinois. Although some evidence exists of occupation during the Late Archaic period (around 1200 BC) in and around the site, Cahokia, as it is now defined, was settled around 600 AD during the Late Woodland period.

|

| Artist’s rendition of Cahokia Mounds. |

The mounds were later named after the Cahokia tribe, a historic Illiniwek people living in the area when the first French explorers arrived in the 17th century. As this was centuries after Cahokia was abandoned by its original inhabitants, the Cahokia tribe was not necessarily descended from the earlier Mississippian-era people. Most likely, multiple indigenous ethnic groups settled in the Cahokia Mounds area during the time of the city's apex. At its peak from 1,100 to 1,200 AD, the city covered nearly six square miles and boasted a population of as many as 100,000 people.

The stockade is one of the principal attractions of the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site and only one of the things about Cahokia on which theories and assumptions diverge. This enormous two-mile-long palisade, which was discovered in excavations in 1966, is described as "encircling the most important sacred area of Cahokia, which includes Monk's Mound, the plaza to the south and several smaller mound groups." Scientists assume this wall to have been started in the time between 900 BCE and 1100 AD and largely completed by about 1150, although additions were made up to 1250.

|

| Cahokia Mounds Stockade display, the right half being covered in clay. |

Its purpose is not exactly known; in general, there are two possible explanations. One of them is that that it functioned as a social barrier, a separation between the most sacred, holy area, a 200-acre Sacred Precinct where the ruling elite lived and was buried, and the rest of the settlement. No matter whether the stockade functioned as a social barrier or was meant as a defensive structure, the assumption is that violence existed in Cahokia.

The Albany Mounds contain evidence of continuous human occupation over the last 10,000 years. The Albany (Illinois) Mounds date from the Middle Woodland period (500BC-500AD), older than either the Cahokia or Dickson Mounds of the Mississippian period. While still obtaining food largely through hunting and gathering, Woodland peoples began practicing the basic horticulture of native plants. They are distinguished from earlier inhabitants by the development of pottery and the building of raised mounds near large villages for death and burial ceremonies.

The only Middle Woodland time-period site owned by the state, Albany Mounds was originally made up of ninety-six burial mounds. At least thirty-nine of the mounds remain in good condition, while eight have been partially destroyed through erosion, excavation, or cultivation. Burial artifacts include non-local materials, indicating the existence of trading networks with Native Indians from other areas. The site of the nearby village remains privately owned. The mounds were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. In the 1990s, the site was “restored" to a natural appearance and a prairie of about one hundred acres was established.

|

| Albany Mounds State Historic Site Map. |

The Kincaid Mounds, located near Brookport, Massac County, Illinois, adjacent to the Ohio River, the site straddles the modern-day counties of Massac County and Pope County in deep southern Illinois, part of an area colloquially known as Little Egypt. The site is 105 acres.

They were ruled by a chief who most likely inherited his position and probably claimed power from the sun. Maize (Corn) farmers in the lowlands along the Ohio River from Hamletsburg upstream to Brookport downstream supported the leaders with grain and constructed the mounds we see today. They also constructed the buildings and the protective wall or palisade that encircled the principal mounds, but which we know only from the archaeological record. The mounds were built in stages over a 350-year period by stacking basket loads of selected soil and clay material one on top of another.

|

| Large buildings atop the main mounds seem to indicate temples or council houses. |

The Pulcher Mounds, occupied from about 800 BC to 900 AD, was named for the mid-20th-century landowner, is in rural Monroe and St. Clair counties, located about 20 miles south of Cahokia near the modern town of Dupo, Illinois. The site was the location of a Middle Mississippian village which was one of the earliest towns contemporary with Cahokia. About 10 mounds are included in the site and a cemetery with stone graves was uncovered.

|

| A stone box grave with jumbled bundled burials at the Pulcher site. |

Much like today’s communities that are connected, the old Indian towns, villages, and farmsteads comprised a network of connectedness via ancient trails and natural waterways. Archaeological excavations at the site have also discovered the remains of houses and garden beds, making the site one of the few Mississippian villages at which garden beds have been found. The site has been known to European settlers since the early settlement of the area in the late 18th century; despite being used for farmland, the site remains in good condition.

The mound site was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 23, 1973.

Dickson Mounds was an Indian site and burial mound complex near Lewistown, Illinois. It is located in Fulton County on a low bluff overlooking the Illinois River. It is a large burial complex containing at least two cemeteries, ten superimposed burial mounds, and a platform mound. The Dickson Mounds site was founded by 800 AD and was in use until after 1250 AD. The site is named in honor of chiropractor Don Dickson, who began excavating it in 1927 and opened a private museum that formerly operated on the site.

|

| This exhibition of the 237 uncovered skeletons uncovered and displayed by Dixon was closed in 1992 by then-Governor of Illinois Jim Edgar. |

|

| A Photo Postcard of Dickson Mounds Cemetery Find. |

|

| Dickson Mounds Location. |

Records show that Dickson Mounds was part of a complex trade network with many culturally diverse populations from the Plains area, the Caddoan area, and Cahokia by 1200 AD. In particular, Cahokia provided Dickson Mounds with luxury items such as copper ornaments and marine shell necklaces in exchange for food items such as meat and fish. The trade of foodstuffs for luxury goods required individuals at Dickson Mounds to generate a surplus of food, resulting in an intensification of agricultural production, which bore serious health and social consequences.

The population at Dickson Mounds is said to have inexplicably vanished during the late thirteenth to the mid-fourteenth century. Possible reasons for the decline of Dickson Mounds are warfare, climate change, and widespread epidemics. Climate change may have had detrimental effects on agriculture, particularly the cultivation of corn, on which the population had become so dependent for subsistence and trade. The significant expansions of the population as well as trade increased contact and transfer of infectious diseases and could also be possible causes of decline.

Chism Mounds was located on the crest of the northern bluffs of Macoupin, County Valley, 1/2 mile north of the creek, which is four miles west of Chesterfield, Illinois.

Gracey Mounds consist of four mounds located on the crest of the bluffs defining the northern edge of Macoupin, County Valley.

Mitchell Mounds was located 7 miles north of Cahokia on a long lake formed from an old channel of the Mississippi River. The site was composed of at least 10 mounds and, being located adjacent to the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, was ideally situated to take advantage of the trade from the north.

Frontier Fortifications

It is a somewhat curious fact that, while La Salle County was the seat of the first fortification, Fort de Crévecoeur, constructed by the French in Illinois that can be said to have had a sort of permanent character, it is also the site of a larger number of prehistoric fortifications, whose remains are in such a state of preservation as to be clearly discernible, than any other section Illinois of equal area.

It is a somewhat curious fact that, while La Salle County was the seat of the first fortification, Fort de Crévecoeur, constructed by the French in Illinois that can be said to have had a sort of permanent character, it is also the site of a larger number of prehistoric fortifications, whose remains are in such a state of preservation as to be clearly discernible, than any other section Illinois of equal area.

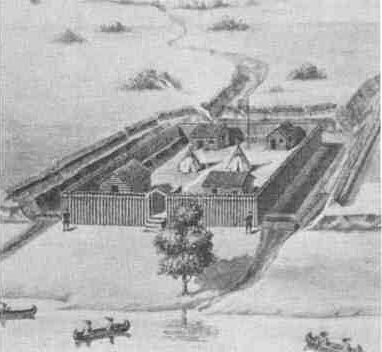

|

| Fort de Crévecoeur. |

One of the most formidable of these fortifications was on the east side of the Fox River, opposite the mouth of Indian Creek and some six miles northeast of Ottawa called Fort Johnston. It occupied a position of decided natural strength and is surrounded by three lines of circumvallation[2], showing evidence of considerable engineering skill. From the size of the trees within this work and other evidence, its age has been estimated at not less than 1,200 years.

Another work of considerable strength was Fort Hubbard. It was erected in 1818 and maintained by the American Fur Company. It stood on the bluff overlooking the Illinois River in the present-day town of Marseilles.

Fort Maillet built-in 1761 was located along the river in modern-day downtown Peoria, then it was used as the American Fur Company trading post. The town was burned out by Americans soldiers in 1812 and the Americans built Fort Clark the following year.

|

| Fort Maillet built in 1761. |

Besides Fort St. Louis du Rocher (on Starved Rock), the outline of Fort Miami and the Village of La Vantum ("the washed") was an Illinois tribe village built on what is called Buffalo Rock. It was located one mile east of Fort St. Louis du Rocher.

|

| Fort Saint Louis du Rocher was built atop Starved Rock on the Illinois River. |

Joseph-Antoine le Fèbvre, Sieur de La Barre, the Governor-General of New France (Canada), gave authority to Louis-Henri de Baugy, Chevalier de Baugy to take control of Fort St. Louis du Rocher on the Illinois River from Henri de Tonti in 1683. In February 1684, the fort was besieged by a force of some 500 Iroquois for eight days. Despite limited ammunition and provisions, the defenders withstood three assaults, and the Iroquois were forced to abandon their attacks and withdraw the way they had come. In 1685, La Salle was given back control of Fort St. Louis du Rocher by the French King Louis XIV. Henri de Tonti erected Fort Miami on Buffalo Rock.

There are two points in Southern Illinois where the aborigines had constructed fortifications to which the name "Stonefort" has been given. One of these is a hill overlooking the South Fork Saline River valley in the southern part of Saline County. Construction of Stonefort, a defensive fortification, is variously attributed to the Spanish soldiers in the sixteenth century, to aboriginal inhabitants preceding the Indians, and even to George Rogers Clark’s company marching to Kaskaskia in 1778. The walls once measured six feet in height, six feet in width, and were arranged in a semi-circle with the southern side an unscalable cliff. The other is on the west side of Lusk's Creek, in Pope County, where a breastwork has been constructed by loosely piling up the stones across a ridge, or tongue of land, with vertical sides and surrounded by a bend of the creek. Water is easily obtainable from the creek below the fortified ridge.

The remains of an old Indian fortification were discovered by early settlers of McLean County, at a point called "Old Town Timber," about 1822 to 1825. It was believed then that it had been occupied by the Indians during the War of 1812. The story was told by the Indians that the fort was burned down by General Harrison in 1812; though this is improbable in view of the absence of any historical mention of the fact. Judge H. W. Beckwith, who examined its site in 1880, is of the opinion that its history goes back as far as 1752 and that it was erected by the Indians as a defense against the French at Kaskaskia. There was also thought to have been been a French mission at this point.

One of the most interesting stories of early fortifications in Illinois is that of Dr. V. A. Boyer, an old citizen of Chicago, in a paper that contributed to the Chicago Historical Society. Although the work alluded to by him was evidently constructed after the arrival of the French in the country, the exact period to which it belongs is in doubt. The fort was located atop a bluff overlooking what was once the old Ausagaunashkee Swamp, a vast, reed-choked marsh that had once stretched from the Desplaines River eastward to the Calumet River. The Forts of Palos, Illinois. Investigations into two fortified sites.

The settlement started as a French trading post by a Potawatomi village sometime in the late 1600s. The French name was "Small Fort River," as translated from French to English. The settlement became known as Little Fort ◄— click to discover the exact location of this fort. The remains of a small fort, supposed to have been a French trading post, were found by the pioneer settlers of Lake County, where the present city of Waukegan stands.

There is also a myth that a fort or trading post called Fort Chécagou came well before the first Fort Dearborn in 1803. Early settlers named the North Branch of the Chicago River the Guarie River [3], or Gary's River, after a trader who may have settled the west bank of the river a short distance north of Wolf Point, at what is now Fulton Street.

|

| A detail from a 1688 map by French-Canadian cartographer Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin includes the first reference to "Fort Chicagou" on a map. The terms had been applied to this area as early as 1681 when René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (Sieur de La Salle being a title only) referred to the area as Chécagou. On a map Franquelin drew in 1684, he seems to have referred to the "River Chéhagou" and the area as Chéagou. |

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Additional Reading: Ancient Illinois Indian Mounds - A Technical Examination.

[1] The Caddoan Mississippian culture was a prehistoric Native American culture considered by archaeologists as a variant of the Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now Eastern Oklahoma, Western Arkansas, Northeast Texas, and Northwest Louisiana.

[2] A circumvallation is a line of fortifications, built by the attackers around the besieged fortification facing toward an enemy fort (to protect the besiegers from sorties by its defenders and to enhance the blockade).

The resulting fortifications are known as 'lines of circumvallation'. Lines of circumvallation generally consist of earthen ramparts and entrenchments that encircle the besieged city. The line of circumvallation can be used as a base for launching assaults against the besieged city or for constructing further earthworks nearer to the city. A contravallation may be constructed in cases where the besieging army is threatened by a field army allied to an enemy fort. This is the second line of fortifications outside the circumvallation, facing away from an enemy fort. The contravallation protects the besiegers from attacks by allies of the city's defenders and enhances the blockade of an enemy fort by making it more difficult to smuggle in supplies.

[3] Guarie River - The first non-indigenous settler at Wolf Point may have been a trader named Guarie. Writing in 1880, Gurdon Hubbard, who first arrived in Chicago on October 1, 1818, stated that he had been told of Guarie by Antoine De Champs and Antoine Beson, who had been traversing the Chicago Portage annually since about 1778. Hubbard wrote that De Champs had shown him evidence of a trading house and the remains of a cornfield supposed to have belonged to Guarie. The cornfield was located on the west bank of the North Branch of the Chicago River, a short distance from the forks at what is now Fulton Street; early settlers named the North Branch of the Chicago River the Guarie River or Gary's River.