|

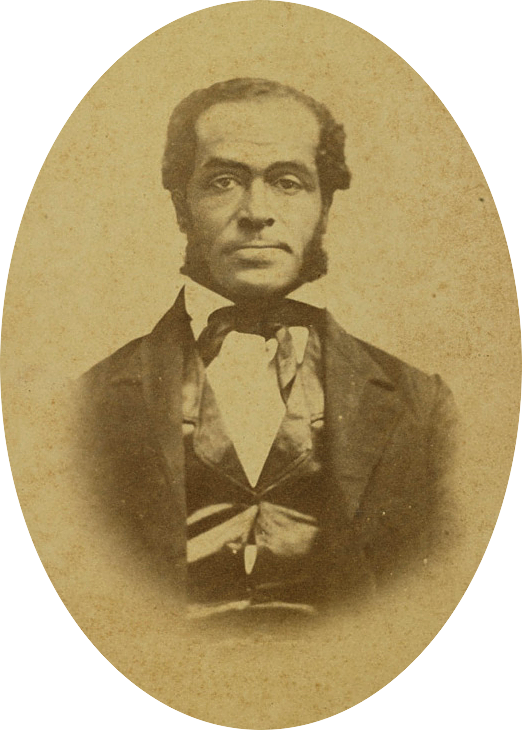

| John L. Jones |

After moving to Chicago, Illinois, in 1845, Jones used his house and office, located on 119 Dearborn Street (today: 609 S. Dearborn), as a stop on the Underground Railroad through Chicago. His home was known as a meeting place for local and national abolitionist leaders including Frederick Douglass and John Brown. He also authored a number of influential anti-slavery pamphlets.

Jones fiercely opposed an anti-immigration provision in the Illinois Constitution of 1848 which would prohibit “free persons of color” from settling in Illinois and bar slaveholders from bringing slaves into Illinois to free them.

Jones pursued the right of equal citizenship and equality before the law “whether his face be black or white,” citing the refusal of the founders to use the word “white” in the U.S. Constitution’s text. Pressure by Jones and like-minded Illinoisans was not enough to halt the provision’s inclusion in the Constitution.

But that setback did not weaken the resolve of Jones to fight Illinois’ black codes. Despite prohibiting slavery within its borders, Illinois kept a scrutinizing eye on its black population through the black laws. According to a contemporary article in Harper’s Weekly, the black laws “were as much a part of the code of slavery as any law of Arkansas or Mississippi.”

The draconian black laws, among other deprivations, prohibited black men from filing suit or being sued; barred blacks from testifying against whites; presumed a black person to be a slave unless he or she could prove to be free; prohibited a black or mulatto from another state from staying in Illinois beyond 10 days, subjecting offenders to arrest, a $50 fine and removal from the state; provided that offenders unable to pay the fine would be sold at auction into servitude until the debt was satisfied; denied black men the right to vote; and denied blacks the right to an education.

On November 4, 1864, John Jones distributes his pamphlet, “The Black Laws of Illinois and a Few Reasons Why They Should Be Repealed,” spurring the General Assembly to repeal all of them.

He called on the General Assembly “to erase (the black laws) from your statute book.” In the 16-page pamphlet, Jones discussed the laws’ evils, relying on legal, economic, moral, and constitutional arguments.

For example, Jones railed against arresting and forcing undocumented blacks “into involuntary servitude, without having committed any crime or offense except being born black” as a violation of due process and imprisonment without trial by jury.

Jones’ essay, according to the Chicago Evening Journal, “has exposed (the black codes) inhumanity and injustice in an able manner … He has the sympathy of all right-thinking men.”

A statewide petition drive followed, and by January, thousands of whites had succumbed to Jones’ campaign.

Within weeks, Gov. Richard J. Oglesby signed the bill repealing the black laws.

The day the repeal took effect, blacks throughout Illinois celebrated. In Springfield, Jones received the honor of igniting a cannon fuse symbolically ending the black laws.

Jones accomplished what no Illinois lawyer who opposed the black laws could. That Jones was black makes this story even more compelling.

Jones learned to read and write with the help of attorney Lemanuel C. Paine Freer, a vehement foe of slavery who befriended Jones soon after Jones arrived in Chicago. In 1869, when blacks in Illinois became eligible for political office, the governor appointed Jones as the state’s first black notary public.

Shortly after the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870, allowing blacks the right to vote in elections, Jones won his first of two terms as a Cook County commissioner, becoming the first black person elected to public office in Illinois.

The end of the black laws did not address the poverty caused by the years that African-Americans had to submit to them. Jones recognized this. He noted, “though the laws are gone, the effects are still visible.”

Jones dedicated his life not only to liberating his people from the curse of the black laws but also helping them surmount the terrible cost in terms of human suffering that the laws inflicted.

Reelected to a full three-year term in 1872, Jones was defeated in his 1875 reelection bid. John Jones died on May 31, 1879, and was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Cook County, Illinois.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.