HENRY VILLARD, FROM A PENNILESS IMMIGRANT TO THE JOURNALIST WHO COVERED ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

|

Henry Villard

13 Years Old |

Born in 1835 to an educated family in the German city of Speyer, Henry had more early advantages than most immigrants. His family was prosperous and well-connected. Politics would help to split the family. When the Liberal Revolution of 1848 began, Henry was only thirteen years of age.

His father stayed loyal to the old aristocratic regime, but other relatives sympathized with the revolutionists. Henry expressed his views when he refused to pray for the King during a service at school. Facing expulsion for his disobedience, Henry’s conservative father saw him as a disgrace to his family.

|

| The failed German Revolutions of 1848-1849 led to a large exodus of refugees. |

Henry was later sent off to study technology at a polytechnic school in Munich. Without telling his father, he instead enrolled in the University of Munich in the literature and writing program. At the end of his term, the eighteen-year-old was confronted with the reality that he soon had to face his father with the news that he had deceived him. He took the money he had left and decided to immigrate to the United States in 1853. It was more appealing to risk death on the high seas than the wrath of his father.

Henry Villard wrote of his first day in America, after disembarking in New York:

“My landing upon American soil took place under anything but auspicious circumstances. I was utterly destitute of money, had but a limited supply of wearing apparel, and that not suited to the approaching cold season, and I literally did not know a single person in New York or elsewhere in the Eastern States to whom I could apply for help and counsel. To crown all, I could not speak a word of English."

|

| Immigrants arriving in New York in the 1850s typically disembarked at South Street. |

Like many newly arrived immigrants, Villard found lodging in the city’s German community, among people who spoke his language. “Our landlord was Max Weber, an ex-officer of the Baden army, who had emigrated in consequence of his participation in the revolutionary outbreak of 1849,” Villard recalled, “He afterward rose to prominence in the War of the Rebellion. Among his regular boarders were several political exiles. These two circumstances made [Weber’s house] a favorite resort of the German refugees then still numerous in New York. Almost every evening there was a gathering of them in the tap-room, where there were noisy political discussions in true German beer-house style. They dwelt upon the Fatherland as well as the United States, and I listened to them with intense interest.” Villard found that the refugees were intensely interested in American politics and society, although they often had little actual experience of the United States beyond the Hudson River.

Villard decided that as intriguing as New York City was, he wanted to see the world to the west:

“I left New York on November 19, with eighteen dollars in my pocket and all my other possessions in a large hand-bag. I had decided to go via Philadelphia and Pittsburg to Cincinnati. My reason for choosing this city as my destination was solely the fact, gathered from my guide-book, that it had a large German population, including a considerable percentage of Bavarians.”

As Villard continued to move across the country he sought out German refugees along the way. Some were warm and friendly, others seemed locked in thoughts of Germany and showed no interest in America. A few were bitterly disappointed by the reality of American democracy.

When Villard got to Chicago he was visited by a step-uncle who reconciled him with the parents Villard had abandoned back in Germany and invited him to Belleville, in St. Clair County, Illinois. Belleville, founded in 1814, was the largest city in Illinois with a population of 2,941 in 1850 (part of the St. Louis Metro Area today) in the southern part of the state at the Mississippi River. At the time, it was a growing center for German immigrants who arrived after the failed Revolution of 1848. The population would more than double between 1850 and 1860. By 1870, 90% of the people living in Belleville would be German immigrants and their children.

Villard placed himself under the care of his uncle Theodore, a Belleville farmer, and his wife. He had never met them before, and his sudden arrival at their home must have been a surprise to them. He remembered his uncle behaving stiffly towards him on their first encounter. As they came to know each other, his uncle and aunt, and their eight children provided a surrogate family for the teenaged Villard. He had difficulties with his own parents in Germany that he did not have here with his immigrant family. “I found myself in a family circle again,” Villard wrote in his Memoirs, “I now felt the softening, elevating influences of this sweet home-life, and a sense of inner peace and happiness awoke in me that I had not felt for years.”

Villard threw himself into farm work and “with these occupations in the daytime, and reading, games, and music in the evening — my aunt and the eldest daughter were very musical — time passed very quickly, and Christmas, 1854, was at hand before we knew it.” The immigrant family brought their Christmas customs from their homeland, “The observance of it was in true German style, with a great tree which the whole family helped to decorate, and there were presents for everybody.”

Belleville was not only home to German immigrants, but it was also a center of German culture in Southern Illinois. Its stores and businesses were modeled on those found in Germany. Villard later recalled the many German beer halls where the men met for an hour or two each week to socialize and talk politics. Villard wrote that “The town had but six or seven thousand inhabitants, and had no special external attractions except that it contained an almost purely German community. I was told that the population included only a few hundred native Americans. We hardly ever heard any English spoken. The business signs were almost exclusively in German.” The fact that it was so German led to its rapid growth; “this very German character of the place and the adjacent settlements made Belleville peculiarly attractive to people of that nationality.”

One of the leading figures of this community was Gustav Koerner. He was a man of the law in Germany who became a refugee following a failed uprising in 1833 that he participated in. Koerner resumed the practice of law in the United States, and took a “lively interest in politics.” He became active in the Democratic Party and “rendered valuable service as a party manager and effective speaker both in English and in German,” according to Villard. American political parties routinely campaigned in English and German in those days. Villard charts Koerner’s amazing career:

“He was elected to both houses of the Legislature, made a circuit judge, and subsequently a member of the Supreme Court, and, finally, Lieutenant-Governor and ex officio President of the Senate. He was then holding that office. When the proslavery tendencies of his party became so pronounced under Presidents Pierce and Buchanan, he assisted in the formation of the Republican party, and remained one of its leaders till after the Civil War.”

Villard writes that Koerner was “intimately acquainted with Abraham Lincoln” and that he represented the U.S. during the Civil War in Madrid.

While Villard loved life in Belleville, he sought a bigger stage. He moved to Chicago in 1856, and that same year he joined the newly emerging anti-slavery party, the Republicans. The city was in the midst of a mayoral election. “I had no right to vote,” Villard tells us in his memoirs, “but that did not prevent me from enlisting as a violent partisan on the anti-Democratic side. The contest was fought directly over slavery.” There were rioting and street fighting at the polls as partisans of each side tried to obstruct their opponents from voting. When the pro-slavery Democrats won, Villard wrote that he “felt woefully depressed in spirit. It seemed to me almost as if the world would come to an end.”

That same year, the Territory of Kansas was becoming a place of conflict between pro- and anti-slavery forces. The territory would soon become a state and the Congress had decreed that the decision on whether slavery would be allowed there would be made by the people living in the territory. Abolitionists and slaveowners began to move to the state to give their side the most votes. Villard conceived a scheme:

“My project was nothing less than the forming of a society among the young Germans throughout the Northwest to secure a large tract of land in Kansas and settle the members upon it. The colony was to be, like the other Northern settlements, a vanguard of liberty, and to fight for free soil, if necessary. Of course, I aspired to be the head of the organization.”

Villard raised a lot of money in Chicago for the project, but not enough to start the colony. He decided to use some of the money to travel East on a fundraising swing through New York and Philadelphia. As his money ran low in he realized he had to abandon his dream. He also came to the grudging conclusion that his financial failure left him in an “awkward position.”

Villard was prevailed upon to take over a failing German-language newspaper in Racine. Wisconsin. A third of the people in the city of 12,000 was German and he thought the paper could succeed. It had been a Democratic Party paper and the Racine Republicans financed the purchase to turn it into a Republican outlet to the German immigrants they hoped to convert.

Most immigrants to the United States in the mid-1800s spoke languages other than English. Many lived and died in the U.S. without ever becoming fluent in English. They wanted to read news of their homelands and their adopted country in the languages they knew from birth. Newspapers in French, Dutch, German, and other languages abounded.

According to Leah Weinryb Grohsgal, the Senior Program Officer at the National Endowment for the Humanities and Coordinator of the National Digital Newspaper Program:

“The first German newspaper printed on American shores predated the Revolution by almost half a century! In fact, the first foreign-language newspaper in the United States was in German—Die Philadelphische Zeitung, begun by Benjamin Franklin in 1732 in his Philadelphia printing shop…these newspapers were critical for maintaining German American identity. For many German immigrants, the emphasis was on the first part of that identity—they were Germans first, and sought to become Americans without relinquishing their German-ness. The group established a pattern that other immigrant groups followed later. They came to America, settled into cultural enclaves, and constructed microcosms of their society in the new country.”

By 1860 there were an estimated 67 German newspapers just in the Old Northwest. Even Lincoln bought a German newspaper in Illinois to try to influence immigrant voters. Multilingual campaigning was an accepted part of American politics by every party except for the Know-Nothings.

|

| In 1856 the new Republican Party ran the first major-party candidate who campaigned against slavery. John C. Fremont was a famous explorer and dashing military man. Although he lost the presidency, his candidacy established the viability of anti-slavery candidates. |

When Villard took possession of the paper, he saw what a mess it was. “There was only an old-style hand press, on which six hundred copies could be printed in a working-day of twelve hours,” he wrote, “The appearance of the paper was indeed wretched, and its contents no better.” The readership itself was suspect. Villard reports that “There were nominally about three hundred and eighty names on the books, but a close examination proved that many of the rural subscribers had either not paid at all for years, or paid in farming produce — butter, eggs, chickens, potatoes, corn, and the like.”

Villard was editing one of only three German Republican newspapers in Wisconsin. There were more than twenty German Democratic papers arrayed against him in the state. The paper was particularly important because Villard published it during the Presidential Election of 1856, the first time a major party candidate, Republican John C. Freemont, ran on an explicitly anti-slavery platform. Villard’s job, he said, was “to persuade the local German voters to go with the Republican party.”

Villard was a practitioner of advocacy journalism. He became totally absorbed in the political campaign and particularly in the organization of immigrant voters. He took on the role of a campaigner to the German-speakers:

“I volunteered to organize a German wing of the local Republican club, and, although this was no easy task, owing to the stolid allegiance of my countrymen to the other party, I succeeded in working up the membership of nearly fifty from the smallest beginnings. We held frequent meetings, which gave me the long-desired opportunity to practice public speaking. I readily got over the first embarrassment, common to all beginners in that art, and acquired considerable fluency. I even addressed some gatherings of German voters especially brought together to listen to me. I was so much encouraged that I even ventured on two occasions on the bold experiment of speaking in English before general meetings of the Republican club.”

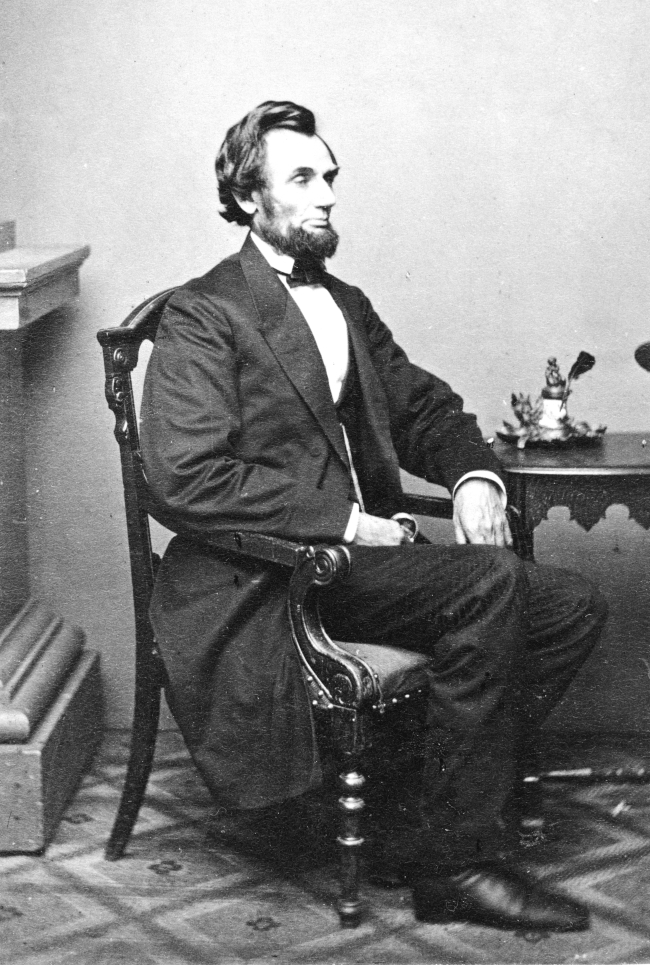

Villard’s growing popularity in Wisconsin brought him to the attention of a German paper in New York. He was soon hired as a Western political correspondent with the Neue Zeit, a progressive paper with a strong women’s rights focus. He was then hired as a contributor by the Staats-Zeitung in New York. This was a German paper of national renown, with the third-largest circulation of any newspaper in any language in New York City. In the male world of newspapers, it was unique in having a woman, Anna Uhl, at its helm. No figurehead, Anna Uhl “was the active business-manager” in Villard’s words. She sent him to cover the Lincoln Douglas Debates in 1858. His reporting there would endear him to Lincoln and make his career.