In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

Africa was a Negro settlement in the northeast corner of Williamson County. It all began when Alexander McCreery came from Kentucky to Thomas Jordan's Settlement, also called Jordan's Fort, southeast of modern Thompsonville, Illinois, in 1812, when he was 14. The following year John McCreery, Alexander's father, followed his son to Illinois.

John brought several family slaves to the territory and settled in what became known as Fancy Farms in Franklin County. The Negros were valued at $10,000 and were held as indentured servants. Under these terms, they were to be freed when they had worked out their worth which complied with the law of the Northwest Territory.

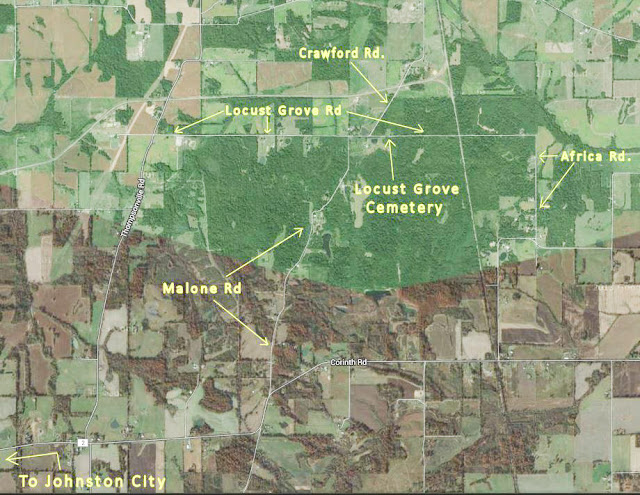

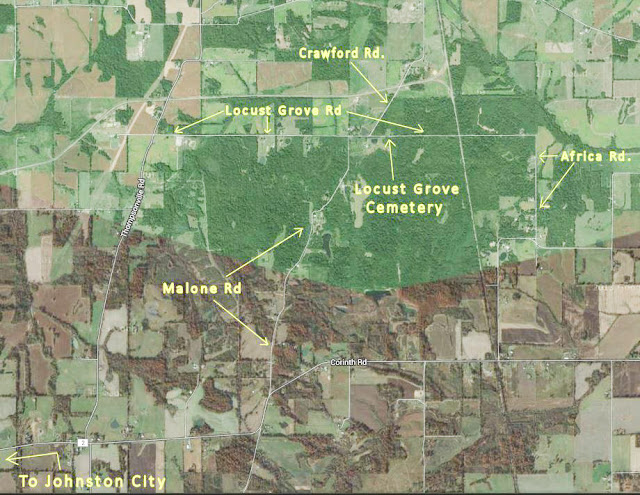

Robert McCreery bought land from the government at 12½¢ cents an acre in what was then the southeast corner of Franklin County. On this land, Robert McCreery built homes for the Negroes, and started "Africa." In 1839, the county was divided, and Williamson County was established from the southern half of Franklin County. This put "Africa" in Williamson County.

Robert McCreery bought land from the government at 12½¢ cents an acre in what was then the southeast corner of Franklin County. On this land, Robert McCreery built homes for the Negroes, and started "Africa." In 1839, the county was divided, and Williamson County was established from the southern half of Franklin County. This put "Africa" in Williamson County.

In 1818, when Illinois Territory became the State of Illinois, there was much opposition to slavery: so much that slavery was barred from the new state by the Constitution. John McCreery decided to take his slaves to Missouri, then a slave state. In 1821, he died. His widow inherited the slaves and remained her property until her death in 1844.

Alexander McCreery, one of her sons, then inherited the slaves. A resident of Illinois, he went to Missouri to take possession. Upon arrival, he learned that all but one had been kidnapped and hidden in the woods. Their captors kept them hidden and watched the road for a chance to run them out of the country and sell them in the South.

With the help of friends, McCreery found his slaves and brought them back from the woods. He discovered that one of the women was married to Richard Inge, a slave who belonged to a neighbor. Not wanting to separate man and wife, Alexander McCreery purchased Inge for three hundred dollars and brought him along with the others to Illinois.

Upon their arrival in Williamson County, McCreery gave them their freedom. They settled in "Africa," where he provided them with land to make their living.

In time, the Negroes who were living in Africa." Decided to build a church of their own. Before this, they had attended church at Liberty, a Methodist Church three miles southeast of Thompsonville. They named their new church, built in 1851 in Locust Grove and affiliated with the Southern Methodist organization.

Later, these inhabitants of "Africa" built a small schoolhouses and employed white teachers to instruct their children. Walter Kent and Miss Annie Simmons were among the white teachers who taught in the school. In later years, Negro teachers were employed, two of whom were William Harrison and John Patton. A lack of funds caused the discontinuance of the school in 1908. The district was then split up and combined with surrounding districts. Now the children go to school with their white neighbors. Later, funds were raised, and the district indebtedness was paid, but the Negro school was never re-established.

One of the freed slaves, Richard Inge, was a shoemaker. He went to Old Frankfort, nearby, and "hired himself" to Ralph Elstum. His shoes were made by hand, and wooden pegs were used. The customer stood on a piece of leather, and Inge marked around his feet to get the size.

Inge was industrious and a good workman. When he had saved enough money, he repaid McCreery for the sum spent to buy his freedom from his Missouri owner. Later, he saved enough to buy eighty acres of land near the Negro settlement.

A woman from Indiana with a small son came to "Africa." Unable to support the boy, she gave him to Inge and his wife, who raised him. Jimmy Hargraves, this boy, still lives in "Africa." He does not know his exact age but believes he is over ninety.

Hargraves proved to his foster parents that he appreciated everything they did for him. A good worker, he cared for them as long as they lived. He was a good cook, serving as camp cook for the railroad construction crews that built the road from Benton to Thompsonville. For twenty-five years, he was a chef in a large Chicago hotel. Many wedding cakes and special dinners were prepared by him for the white residents of the communities around "Africa."

Just before the Civil War, feeling ran high, and some Southern sympathizers warned the Negroes of "Africa" to leave their homes. Frightened, three wagon loads of them, with most of their family possessions, started up the old Sarahsville road, past Liberty Church, on their way out of the region.

It was Sunday morning, and the church members gathered for Sunday School and found out what was happening. They persuaded the Negroes to return home, promising they would not be molested. The Negroes turned back, and the Southern sympathizers were not heard from again.

These Negroes of "Africa" never have been a detriment to the communities around them. They have been self-supporting and have attended to their own affairs. Some have taken advantage of all the opportunities that have come their way. Several had finished high school, and a few had attended college. Miss Ary Dimple Bean completed her high school work at Marion and graduated, in 1924, from a two-year college at Southern Illinois Normal University.

The settlement was not as large as it once was, but at the present time, it covers 540 acres, with about forty persons living there. In all the years of its existence, it never Incorporated as a town. The inhabitants are almost universally farmers, and their economic status is now and always has been up to the level of white citizens. Jerry Bean was the most progressive farmer in the settlement at this time.

Today three farms are owned by Negro people, but none live in the community. These farms are owned by Allens, Adams, and Dimples Craig. The church is still standing but has been vandalized by inconsiderate people many times. There are no regular services at the church, but once a year, on Memorial Day, it is the sight of a homecoming. This is a day when friends meet, when graves of loved ones are decorated with flowers, and barbequed meat is prepared and sold to raise money for the church and cemetery upkeep.

The churchyard grave markers bear the names of old settlement pioneers — Stewart, Harrison, and Martin. Morris Stewart, buried in 1890, seems to be the first burial. However, there is an older burial ground southeast of the church.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

Africa was a Negro settlement in the northeast corner of Williamson County. It all began when Alexander McCreery came from Kentucky to Thomas Jordan's Settlement, also called Jordan's Fort, southeast of modern Thompsonville, Illinois, in 1812, when he was 14. The following year John McCreery, Alexander's father, followed his son to Illinois.

|

| There are no regular services at the church now, but once a year, on Memorial Day, it is the sight of the community's homecoming. |

In 1818, when Illinois Territory became the State of Illinois, there was much opposition to slavery: so much that slavery was barred from the new state by the Constitution. John McCreery decided to take his slaves to Missouri, then a slave state. In 1821, he died. His widow inherited the slaves and remained her property until her death in 1844.

Alexander McCreery, one of her sons, then inherited the slaves. A resident of Illinois, he went to Missouri to take possession. Upon arrival, he learned that all but one had been kidnapped and hidden in the woods. Their captors kept them hidden and watched the road for a chance to run them out of the country and sell them in the South.

With the help of friends, McCreery found his slaves and brought them back from the woods. He discovered that one of the women was married to Richard Inge, a slave who belonged to a neighbor. Not wanting to separate man and wife, Alexander McCreery purchased Inge for three hundred dollars and brought him along with the others to Illinois.

Upon their arrival in Williamson County, McCreery gave them their freedom. They settled in "Africa," where he provided them with land to make their living.

In time, the Negroes who were living in Africa." Decided to build a church of their own. Before this, they had attended church at Liberty, a Methodist Church three miles southeast of Thompsonville. They named their new church, built in 1851 in Locust Grove and affiliated with the Southern Methodist organization.

Later, these inhabitants of "Africa" built a small schoolhouses and employed white teachers to instruct their children. Walter Kent and Miss Annie Simmons were among the white teachers who taught in the school. In later years, Negro teachers were employed, two of whom were William Harrison and John Patton. A lack of funds caused the discontinuance of the school in 1908. The district was then split up and combined with surrounding districts. Now the children go to school with their white neighbors. Later, funds were raised, and the district indebtedness was paid, but the Negro school was never re-established.

One of the freed slaves, Richard Inge, was a shoemaker. He went to Old Frankfort, nearby, and "hired himself" to Ralph Elstum. His shoes were made by hand, and wooden pegs were used. The customer stood on a piece of leather, and Inge marked around his feet to get the size.

Inge was industrious and a good workman. When he had saved enough money, he repaid McCreery for the sum spent to buy his freedom from his Missouri owner. Later, he saved enough to buy eighty acres of land near the Negro settlement.

A woman from Indiana with a small son came to "Africa." Unable to support the boy, she gave him to Inge and his wife, who raised him. Jimmy Hargraves, this boy, still lives in "Africa." He does not know his exact age but believes he is over ninety.

Hargraves proved to his foster parents that he appreciated everything they did for him. A good worker, he cared for them as long as they lived. He was a good cook, serving as camp cook for the railroad construction crews that built the road from Benton to Thompsonville. For twenty-five years, he was a chef in a large Chicago hotel. Many wedding cakes and special dinners were prepared by him for the white residents of the communities around "Africa."

Just before the Civil War, feeling ran high, and some Southern sympathizers warned the Negroes of "Africa" to leave their homes. Frightened, three wagon loads of them, with most of their family possessions, started up the old Sarahsville road, past Liberty Church, on their way out of the region.

It was Sunday morning, and the church members gathered for Sunday School and found out what was happening. They persuaded the Negroes to return home, promising they would not be molested. The Negroes turned back, and the Southern sympathizers were not heard from again.

These Negroes of "Africa" never have been a detriment to the communities around them. They have been self-supporting and have attended to their own affairs. Some have taken advantage of all the opportunities that have come their way. Several had finished high school, and a few had attended college. Miss Ary Dimple Bean completed her high school work at Marion and graduated, in 1924, from a two-year college at Southern Illinois Normal University.

The settlement was not as large as it once was, but at the present time, it covers 540 acres, with about forty persons living there. In all the years of its existence, it never Incorporated as a town. The inhabitants are almost universally farmers, and their economic status is now and always has been up to the level of white citizens. Jerry Bean was the most progressive farmer in the settlement at this time.

Today three farms are owned by Negro people, but none live in the community. These farms are owned by Allens, Adams, and Dimples Craig. The church is still standing but has been vandalized by inconsiderate people many times. There are no regular services at the church, but once a year, on Memorial Day, it is the sight of a homecoming. This is a day when friends meet, when graves of loved ones are decorated with flowers, and barbequed meat is prepared and sold to raise money for the church and cemetery upkeep.

The churchyard grave markers bear the names of old settlement pioneers — Stewart, Harrison, and Martin. Morris Stewart, buried in 1890, seems to be the first burial. However, there is an older burial ground southeast of the church.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.