When Richard was 15, his father lost his substantial fortune in a stock farm venture; his father died two years later. Young Richard then took a job in the general offices of the Minneapolis and St. Paul Railroad to help support his widowed mother and his sisters.

Once he had qualified as a station agent Sears asked to be transferred to a smaller town in the belief that he could do better there financially than in the big city. Eventually, he was made station agent in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, where he took advantage of every selling opportunity that came his way. He used his experience with railroad shipping and telegraph communications to develop his idea for a mail-order business.

As a railroad station agent in a small Minnesota town, Sears lived modestly, sleeping in a loft right at the station and doing chores to pay for his room and board. Since his official duties were not time-consuming, Sears soon began to look for other ways to make money after working hours. He ended up selling coal and lumber and he also shipped venison purchased from Native American tribes.

The strategy worked and before long Sears was buying more watches to sustain a flourishing business. Within just a few months after he began advertising in St. Paul, Sears quit his railroad job and set up a mail-order business in Minneapolis that he named the R. W. Sears Watch Company.

Offering goods by mail rather than in a retail store had the advantage of low operating costs. Sears had no employees and he was able to rent a small office for just $10 a month. His desk was a kitchen table and he sat on a chair he had bought for 50¢. But the shabby surroundings did not discourage the energetic young entrepreneur. Hoping to expand his market, Sears advertised his watches in national magazines and newspapers. Low costs and a growing customer base enabled him to make enough money in his first year to move to Chicago and publish a catalog of his goods.

In Chicago Sears hired Alvah C. Roebuck to fix watches that had been returned to the company for adjustments or repairs. The men soon became business partners and they started handling jewelry as well as watches. A master salesman, Sears developed a number of notable advertising and promotional schemes, including the popular and lucrative "club plan." According to the rules of the club, 38 men placed one dollar each week into a pool and chose a weekly winner by lot. Thus, at the end of 38 weeks, each man in the club had his own new watch. Such strategies boosted revenues so much that by 1889 Sears decided to sell the business for $70,000 and move to Iowa to become a banker.

Sears soon grew bored with country life, however, and before long he had started a new mail-order business featuring watches and jewelry. Because he had agreed not to compete for the same business in the Chicago market for a period of three years after selling his company, Sears established his new enterprise in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He hired Roebuck again and this time he dubbed the product of their partnership A. C. Roebuck and Company. In 1893 Sears moved the business to Chicago and renamed it Sears, Roebuck, and Company.

Once established in Chicago, the company grew rapidly. The first edition of the Sears catalog published in the mid-1880s had included a list of only 25 watches.

By 1892, however, it had expanded to 140 pages offering "everything from wagons to baby carriages, shotguns to saddles." Sales soared to nearly $280,000. A mere two years later the catalog contained 507 pages worth of merchandise that average Americans could afford. Orders poured in steadily and the customer base continued to grow. By 1900 the number of Sears catalogs in circulation reached 853,000.

Sears was the architect of numerous innovative selling strategies that contributed to his company's development. In addition to his club plan, for example, he came up with what was known as the "Iowazation" project: the company asked each of its best customers in Iowa to distribute two dozen Sears catalogs. These customers would then receive premiums based on the amount of merchandise ordered by those to whom they had distributed the catalogs. The scheme proved to be spectacularly successful and it ended up being used in other states, too.

Richard Sears had a genius for marketing and he exploited new technologies to reach customers nationwide via mail-order. At first, he targeted rural areas: People had few retail options there and they appreciated the convenience of being able to shop from their homes. Sears made use of the telegraph as well as the mails for ordering and communicating. He relied on the country's expanding rail freight system to deliver goods quickly; the passage of the Rural Free Delivery Act made servicing remote farms and villages even easier and less expensive.

Such tremendous growth led to problems, however. While Sears was a brilliant marketer (he wrote all of the catalog material), he lacked solid organizational and management skills. He frequently offered merchandise in the catalog that he did not have available for shipment, and after the orders came in he had to scramble to find the means to fill them. Workdays were frequently 16 hours long; the partners themselves toiled seven days a week. Fulfilling orders accurately and efficiently also posed a challenge. One customer wrote, "For heaven's sake, quit sending me sewing machines. Every time I go to the station I find another one.

You have shipped me five already." Roebuck became exhausted by the strain of dealing with these concerns and he sold his interest in the company to Sears in 1895 for $25,000.

By 1895 the company was grossing almost $800,000 ($26.8 million today) a year. Five years later that figure had shot up to $11 million ($368 million today), surpassing sales at Montgomery Ward, a mail-order company that had been founded back in 1872.

In 1895 Sears married Anna Lydia Mechstroth of Minneapolis and they had three children.

In 1901 Sears and Rosenwald bought out Nussbaum for $1.25 million ($50 million today).

By 1906, for example, Sears, Roebuck was averaging 20,000 orders a day. During the Christmas season, the number jumped to 100,000 orders a day. That year the company moved into a brand-new facility with more than three million square feet of floor space. At the time it was the largest business building in the world.

Beginning in 1908 Sears, Roebuck and Co. sold mail-order Modern Homes program. Sears was not an innovative home designer. Sears was instead a very able follower of popular home designs but with the added advantage of modifying houses and hardware according to buyer tastes. Individuals could even design their own homes and submit the blueprints to Sears, which would then ship off the appropriate precut and fitted materials, putting the homeowner in full creative control. Modern Home customers had the freedom to build their own dream houses, and Sears helped realize these dreams through quality custom design and favorable financing.Over the next 32 years, Sears designed 447 different housing styles, from the elaborate multistory Ivanhoe, with its elegant French doors and art glass windows, to the simpler Goldenrod, which served as a quaint, three-room and no-bath cottage for summer vacationers. (An outhouse could be purchased separately for Goldenrod and similar cottage dwellers.) Customers could choose a house to suit their individual tastes and budgets. Production ended in 1940 and Sears sold about 70,000 - 75,000 homes.

The History of Sears Modern Homes and Sears Honor Bilt Homes includes Floor Plans.

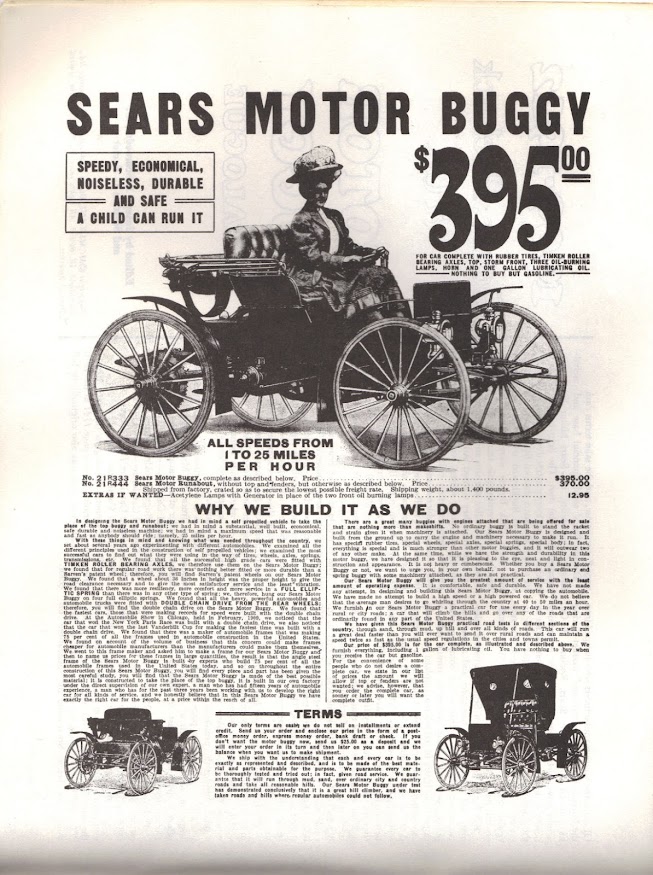

In the initial production year of 1909, the Sears Motor Buggy was offered only as a $395.00 ($12,000 in today's dollars), solid-tired, runabout. But starting in 1910, Sears offers 5 different models of the automobile. The truth of the matter is that they were all basically the same car with different amenities, like fenders, lights, tops, etc.

Richard Sears resigned as president of the company he had founded in 1909. His health was poor and many of his extravagant promotional schemes had begun to run into opposition from his fellow executives, including Rosenwald. He turned the company over to his partner and retired to his farm north of Chicago. At the time of his death on September 28, 1914, Sears left behind an estate of $25 million ($703 million today) and an enduring legacy of success in the highly competitive world of retailing.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ is RATED PG-13. Please comment accordingly. Advertisements, spammers and scammers will be removed.