In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

This Indian society is known to itself as the Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquakie) or "People of the Red Earth." While there are variant spellings of the name." Neighboring Indian tribes referred to them as the “Outagami.” The French more commonly employed the name “Renard,” which in English becomes Fox.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

|

| The Meskwaki (Fox) Indian Tribe. |

Father Druillettes reports, "The two Frenchmen who have made the journey to those regions say that these people are of a very gentle disposition." At the time of contact, there may have been 1000 warriors with a total population of perhaps 2500. The French trader and adventurer Perrot were perhaps the only Frenchman to successfully interact with the Meskwaki. The exploitive and unscrupulous actions and sense of superiority of the French permanently disaffected them from French culture.

Meskwaki hunting parties ranged into northern Illinois, however, and in 1669 Jesuit priests reported that Meskwaki hunters encamped along the Des Plaines River in western Cook County had been mistaken for a Potawatomi tribe and had been attacked by a war party of Iroquois. Although they continued to reside in Wisconsin, by 1700, Meskwaki hunters frequently descended the Fox River Valley to hunt bison on the prairies of northern Illinois. Large numbers of Meskwaki also passed through the Chicagou region in 1710 when part of the tribe temporarily moved to the Detroit region.

In the first half of the eighteenth century, the Meskwaki became embroiled in at least three major periods of conflict with the French. From the French perspective, the Mesuqakies consistently blocked French economic interests and spread dissension and conflict among the Indians of the region.

A military confrontation between the Meskwaki and French at Detroit in 1712 ushered in a quarter-century of Meskwaki-French warfare. Although the Meskwaki returned to Wisconsin in 1712, Meskwaki Warriors continued to scour the Chicago region, attacking French traders, woodsmen, and French-allied Indians. After the defeat of the Meskwaki at Detroit, they preyed upon the French and their Indian allies throughout the upper Illinois country for four years.

On December 1, 1715, a Meskwaki war party led by Pemoussa (He Who Walks) attacked a French expedition led by Constant Le Marchand de Lignery and, in a series of skirmishes along the lakefront, drove the French and their allies back toward Michigan. The Meskwaki and French warfare flared intermittently for over a decade. Meskwaki war parties so disrupted the French fur trade in northern Illinois and Wisconsin that the French sent several additional expeditions against the Meskwaki villages.

During the period from 1719 to 1726, the Meskwaki were again at war with the Illinois and, by virtue of this, the French. Their raids extended as far as Fort de Chartres in southern Illinois. In 1726, in spite of a confused response on the part of the French, a formal peace was concluded.

By 1727 the French were again expanding trade with the Sioux and other societies of the upper Mississippi basin. French success in this venture depended on water routes cutting through central Wisconsin, hence the heart of the Meskwaki homeland. The Meskwaki resisted this incursion. The French response during this final period of conflict was attempted genocide. This policy culminated with the Meskwaki defeat on the prairies of east-central Illinois after a twenty-three-day siege.

The French campaigns achieved some success. During the summer of 1730, some of the Meskwaki attempted to abandon their villages in Wisconsin and pass through northern Illinois en route to joining the Senecas in New York. These Meskwaki descended the Fox River Valley just west of Chicago, crossed the Illinois River near Starved Rock, and traveled southeastward across the prairies in early August.

Over the course of several days, the Meskwaki built a defensive fort in the middle of a small grove of trees along the bank of the Sangamon River, surrounded by nearly two miles of open prairie. The fort was about 150 feet wide and 350 feet long. There were three walls with the Sangamon Riverside left open. They believed they had ample supplies of food and gunpowder and that the native tribes would not want to engage them in a long siege.

The French and their allies came upon the Meskwaki by the vicinity of today’s Village of Arrowsmith, formerly known as "Smith's Grove," in McLean County and not near Starved Rock, as many historical accounts claim. The Meskwaki took refuge in their new Fort, and after a 23-day siege, they broke through the French lines but were attacked and defeated by their enemies. They lost two hundred warriors and about three hundred women and children. This was the only battle ever fought in McLean County, Illinois.

|

| Map of Meskwaki Conflict. |

It was back about the same time that White Robe lived; it happened in 1732 in Illinois when the Meskwaki were surrounded in the forest. We were surrounded on all sides by other Indian tribes and by the French and we couldn't get away.

There were two leaders. And they took the sacred bundle and started leading a song, a sacred song. And they drummed and they sang and they chanted until the other side all fell asleep.

We had two runners, what you might call messengers. We don't have them any longer. And these two runners took a sacred wolf skin down to the river. And they were supposed to drag it lightly across the river to produce a fog.

But I guess they got overanxious in their duty and they dipped it in the water, dipped it in so that it was all covered up with water. On the top of it: they dunked it in the water. I guess they wanted to be sure that it would work. But instead it produced too much fog - a lot of rain and a lot of moisture in the air.

So while these people were all sleeping, the Meskwaki were to crawl away through this fog. As we were crawling over these sleeping bodies, we were being led by these two men who had taught us how to get away. One man's name was Mamasa: he was the drummer who had helped put the enemy to sleep. And the other man's name, I can't remember.

But as our people were crawling over the sleeping bodies, the fog was so thick that we couldn't see each other. So in the middle of the line, somebody lost a hand hold and we couldn't see each other, so one group went in one direction and the other group went in the other direction. And the other group got lost from us.While this narrative does little to pinpoint the location of Meskwaki Fort, it is intriguing in its own right. During this period, the Meskwaki were surrounded and heavily outnumbered by the French four times. On three of these occasions, they were able to employ the weather (a fog, a rainstorm, and a snowstorm) to escape and survive. Moreover, all of the French accounts of the siege remark on the singular nature of the storm that struck on the night of September 8, 1730. De Villiers states that it suddenly began an hour before sunset and lasted into the night "...so that, in spite of all I could say to our savages, I was unable to make them guard all the outlets." Reaume's narrative adds that the Meskwaki "...made a large fire... " inside their fort that night and thus forewarned him of their escape plans.

Following additional attacks upon their remaining villages in Wisconsin, in 1732, the Fox refugees established a new, heavily fortified village on Pistakee Lake, northwest of Chicago, astride the modern boundary between Lake and McHenry Counties. In October 1732, led by the war chief Kiala, the Meskwaki successfully defended this village against a large war party of French-allied Indians. However, during the following spring, they abandoned the village and returned to Wisconsin, where they sought sanctuary among the Sacs at Green Bay.

By 1733 fewer than 100 Meskwaki remained alive.

After 1733 the Meskwaki and Sacs lived together, first in Wisconsin, then in the lower Rock River Valley of northwestern Illinois, and finally in Iowa. A small village of Meskwaki reoccupied the Chicago region in 1741, but one year later, they rejoined their kinsmen near Rock Island.

Today, tribespeople from the Meskwaki Settlement near Tama, Iowa, form part of the modern Indian community clustered in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood.

French Accounts

While several documents that make reference to the siege are available in the published literature, only two may be properly considered primary accounts. One is the official report filed by Lieutenant Nicolas-Antoine Coulon de Villiers, Commandant at the River St. Joseph and commander of the French forces. The other is an unattributed narrative authored by a Fort de Chartres source under the direction of Lieutenant Robert Groston de St. Ange. De Villiers' account is dated September 23, 1730. It was carried to Quebec by his son, Louis Coulon de Villiers, and the interpreter, Jean-Baptiste Reaume. They delivered it to Charles de La Boische de Beauharnois, Governor of New France. The Fort de Chartres version is dated September 9, 1730, and was issued in New Orleans.

In the spring of 1989, a third narrative of the battle was identified in the Archives Nationales in Paris, France. The existence of the document had been suggested in a letter to the Minister of Marine from Giles Hocquart, Intendant of New France. It is dated November 14, 1730. In the missive, Hocquart indicates an "annexed relation" of the siege based upon his interview with Jean-Baptiste Reaume, de Villiers' interpreter. Hocquart even allows that he had "...retained the expressions of the Sieur Reaume which are according to Canadian usage." Hocquart's suggestion that it "...contains some details omitted by Monsieur Devilliers" is accurate from both history and archaeology perspectives.

The document is dated November 7, 1730, and was issued from Quebec. It thus precedes Hocquart's letter by a week. From the first paragraph, it is apparent that the informant and central character in the narrative is Jean-Baptiste Reaume, "...interpreter for the savages that dwell along the River St. Joseph." The account was transcribed by D'Auteuil de Monceaux. The document had been filed under a misspelling of his name. In a 1722 letter from Vaudreuil, Governor of New France, Auteuil is accused of being an immoral consort to the marriage of Jean-Baptiste Reaume's brother, Simon. Both Jean-Baptiste and Simon play major roles in the account.

The three accounts agree in general chronology and offer useful detail on the natural setting of the site and the architecture of the fort, and the strategy and internal politics of the allied forces. In July, the Meskwaki had captured several Cahokias near Fort St. Louis Le Rocher (Starved Rock) on the Illinois River and had burned the son of one of their chiefs. Angered, the Cahokias sent runners to Fort de Chartres seeking support. The Potawatomi, Kickapoos, Mascoutens, and The Illinois had also been attacked by the Meskwaki.

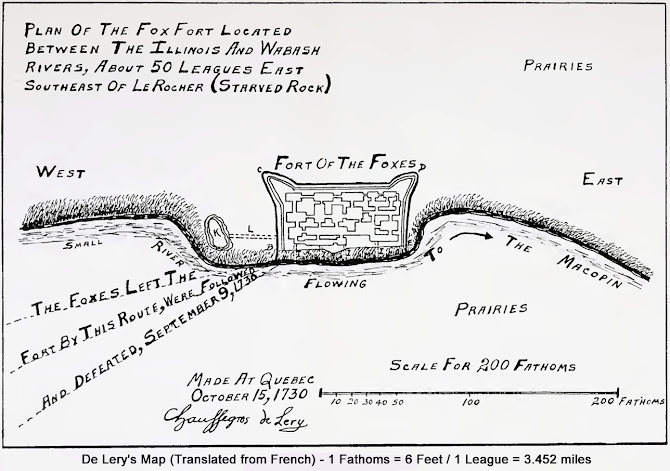

The Illinois had pursued the Meskwaki and found them marching east toward the Ouiatanons (west-central Indiana). Upon contact, The Illinois engaged the Meskwaki, who took possession of a small grove of trees and therein fortified themselves. (The Reaume narrative is the only one to provide a distance and direction reference to the fort. The interpreter places the site 50 leagues [1 League = 3.45 Miles] southeast of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher.) The next day runners were sent to the Miami post and to the St. Joseph command to report the fort's location and direct their support. The Fort de Chartres account indicates that the allied Indian forces had been awaiting aid for a month prior to the arrival of the French.

By August 10th St. Ange was moving north with 500 men and de Villiers southwest with 300. They joined with the 200 already present at the site. Another group of 400 Ouiatanons and Peanguichias under the command of Simon Reaume (Reaume Narrative) arrived the same day as de Villiers, bringing the total to about 1400 men at arms. St. Ange was the first to arrive (August 17th), with the rest of the forces arriving shortly after on August 20th.

According to the Fort de Chartres narrative, the Meskwaki fort was in:

...a small grove of trees surrounded by a palisade situated on a gentle slope rising on the west and north west side on the bank of a small river, in such manner that on the east and south east sides they were exposed to our fire. Their cabins were very small and excavated in the earth like the burrows of the foxes from which they take their name.For his part, de Villiers offers the following description of the enemy's position:

The Renards' fort was in a small grove of trees, on the bank of a little river running through a vast prairie, more than four leagues in circumference, without a tree, except two groves about 60 arpents {an old French unit of land area equivalent to about 1 acre} from one another.He also adds that the Meskwaki had ditches on the outside of their fort.

The Reaume account adds little to the description of the natural environment, suggesting only the woods located in a "...prairie as far as the eye could see." However, it provides some interesting detail on the fortification:

The Renards fortified themselves in their woods and the allies in the prairie a half a league from each other. The Renard fort was of stakes a foot apart, crossed at the top, all joined together and filled in with earth between them as high up as the crossing. On the outside a ditch ran around three sides with branches planted to hide it, with pathways of communication for the fort in the ditches and others that ran to the river. Their cabins were complete with joists covered with decking, commonly called straw mats (natter de paille). On top of this there was two to three feet of earth, depending on the cabin. They were covered in ways such that one could see only an earthwork (terrasse) that would cast a shadow in the fort.The main encampment of St. Ange was to the south of the river. This group positioned three redoubts and attendant trenches so as to command the river and deny the Meskwaki access to water. De Villiers' primary encampment was to the northeast or north of the Meskwaki fort. His forces constructed two cavaliers on the high ground overlooking the fort and an attack trench from which he hoped to set fire to the fort.

During the ensuing siege, the Allied forces were plagued with internal intrigues, shifting sympathies, and intertribal conflicts. The French alliance was a fragile one. On September 1st, Nicolas des Noyelles arrived with 100 men from the Miami Post. On September 7th, 200 of The Illinois deserted.

On the eighth of September, a terrible storm blew up, and as the Fort de Chartres narrative records, "...interrupted our work." The night was rainy, foggy, and very cold. The allied Nations refused to man their posts. Seizing this opportunity, the Meskwaki escaped from their fort. However, the crying of the children alerted the French sentries, and their flight was discovered. Fearful that their own allies would fire upon them in a night engagement, the French command determined to wait until daybreak before launching their assault. At dawn, some eight leagues from the fort (Reaume narrative), they rushed the exposed Meskwaki. Their ranks were immediately broken and defeated. The Reaume account further states that 500 were killed and 300 captured, and forty of the captured warriors were "burned." The Fort de Chartres narrative adds that not more than 50 or 60 unarmed men escaped.

Maps and Sketches

At least six maps of the siege are known to survive, as well as a planned view of the fort with a number of appended details. The official map of the battle camp (there are two drafts) and the plan of the fort with the appended details are signed by Chaussegros de Lery (respectively titled Blocus du Fort and Plan du Fort des Sauvages). De Lery was the chief military engineer of New France and was responsible for the official documents. De Lery's informants were de Villiers' son, Coulon, and the interpreter, Jean-Baptiste Reaume. These interviews occurred in Quebec when the two reported de Villiers' victory. The documents are variously dated November 10, 11, and 15 of 1730.

|

| Bastioned plan close-up |

|

| Digrams of house, parapet, and fosse construction. |

Peyser (1987) has offered an extensive analysis of the two remaining charts. In light of the Reaume account, Fort des Renards and Sauvages Renards Attaques seem circumstantially associated with it. The references in the narrative correspond to those of the maps, placing as they do a singular emphasis on the roles of the Reaume brothers. It should be noted, however, that while the Hocquart communication references an appended narrative, it does not mention a map. Neither is signed or dated. Consequently, how these maps found their way to the records of the Minister of Marine remains open.

The present author has previously discussed the enigmatic variation between these several drawings regarding the basic geometry of the fort (Stelle 1989). In further addressing this difficulty, some new perceptions and possibilities have emerged. The Fort des Renards and the Sauvages Renards Attaques (Map 1 and Map 2, respectively) appear related not only in historical perspective but also with regard to artistic representation.

|

| CLICK MAP 2 FOR A FULL-SIZE VIEW. Sauvages Renards Attaques. Undated and unsigned, it is attributed to the Reaume Narrative by the present author. |

In spite of the intriguing linkages suggested in the foregoing discussion, which representation of the fort is correct remains unknown. The methods of historiography fail to provide an answer to this critical issue. The real promise of archaeology for history is that answers to questions of historical speculation are potentially available in the ground and can be determined upon the application of proper archaeological techniques. In this case, the validity of the drawings has the potential for empirical determination.

Proposed Locations

The same consideration applies to the actual location of the fort. As previously indicated, the poverty of colonial cartography and the absence of useful landmarks on the prairie have left the answer to this question problematic. At least ten tracts are offered in the literature as the site of the fort. Authors have chosen their locations on the basis of their perceptions of the veracity of the historical documents and their interpretation of distance and direction measurements. All distance and direction references are generalized and presumably reflect surface rather than statute distances. This ambiguity has left much room for historical speculation.

Only the newly surfaced Reaume Narrative provides a distance and direction reference of the three narratives. The other two are surprisingly silent with regard to this central fact. Reaume indicates that the Meskwaki were found "...50 leagues (173 miles) southeast of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher."

|

| CLICK MAP FOR FULL-SIZE VIEW |

|

| CLICK MAP FOR FULL-SIZE VIEW |

|

| CLICK MAP FOR FULL-SIZE VIEW |

(1) the legend of de Lery's Blocus du Fort and Plan du Fort des Sauvages.

(2) a letter from Hocquart to the French Minister of Marine, dated January 15, 1731.

(3) a detail in the map Sauvages Renards Attaques. De Lery indicates that the fort was located 50 leagues east southeast of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher.

Hocquart's report states "...in a plain situated between the Wabache and the Illinois rivers, about 60 leagues to the south of the extremity or foot of Lake Michigan, to the east-south-east of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher in the Illinois Country."

Lastly, the detail on the Sauvages Renards Attaques chart indicates that the fort was located on the River of the Renards or the Beiseipe River, which flowed into the Mabichi River. The Mabuchi, in turn, emptied into the greater Wabash River. The detail further adds that this river system extended to within 40 leagues of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher and was located to the southeast.

What seems consistent about these descriptions is a location southeast or east southeast of Fort St. Louis Le Rocher some 40 to 50 leagues in a then unmapped region of Illinois. With river systems uncharted at the time and river names unrecognizable today, these referents are of little direct use.

An article on May 18, 1897, in Pantagraph Newspaper confirms that a fort's outlines (breastwork) still existed. October 9, 1901, Daily Bulletin reports a few miles west of Cheney's Grove and southeast of the Village of Arrowsmith on a small tract of land, not over ten acres, evidence was found of an early battlefield.

|

| Brass metal fragments were found on the battlefield. |

|

| Fort du Renards Battle Site after Two Hundred Years. |

|

| An engraved boulder was unveiled Sunday on the Roy Smith farm near the Village of Arrowsmith, Illinois, marking Etnataek, the site of a bloody Indian-French battle in 1730. Etnataek is Algonquin for “where fight, battle or clubbing took place.” After the extensive historical study, William Brigham of Bloomington (above), Historian and former superintendent of schools, established the battle site in the Arrowsmith area. Modern historians and archaeologists no longer use the French term Etnataek to describe the site. 1951 |

|

| This peaceful landscape in eastern McLean County was the scene of a bloody 1730 siege of Fox Indians by the French and their Indian allies. Photo shot in 2007. |

No comments:

Post a Comment

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ is RATED PG-13. Please comment accordingly. Advertisements, spammers and scammers will be removed.