Abraham Lincoln's log cabin “rail-splitter” provenance was well known, and it helped make him hugely popular with average voters hungry for a new political hero. Despite his lack of family pedigree, fortune, or schooling, Lincoln made a career of being underestimated, overcompensating with a brilliant, active intellect. The farmboy turned president especially loved innovations and inventions. Lincoln is the only U.S. president to win a patent – No. 6469, issued in May 1849 for a “Method of Buoying Vessels Over Shoals.”

Lincoln’s natural interest in things mechanical would come to be tested — and celebrated — in the Civil War. The North’s huge advantage in men and technology was only as good as the tools of war that Lincoln’s Bureau of Ordnance was able to place into those men’s hands.

The president took a particular interest in rifles and ammunition as well. Infantry warfare was quickly making the transition from the smoothbore muskets that won the Revolutionary War to “rifled” weapons that were more accurate, with greater range and firepower. While the smoothbores could still be effective in close quarters, inventors and arms manufacturers sought ways to increase the distance and speed with which soldiers could fight more effectively.

One such inventor was Christopher Miner Spence of Connecticut. Spencer learned the machinist’s trade as a 14-year-old apprentice at a silk manufacturing company and later worked at the Samuel Colt factory in Hartford, where he learned how to make fire-arms. The Colt factory was famous for pistols and other sidearms, but Spencer became convinced of the feasibility of designing a breech-loaded repeating rifle that could be reloaded easily and rapidly.

|

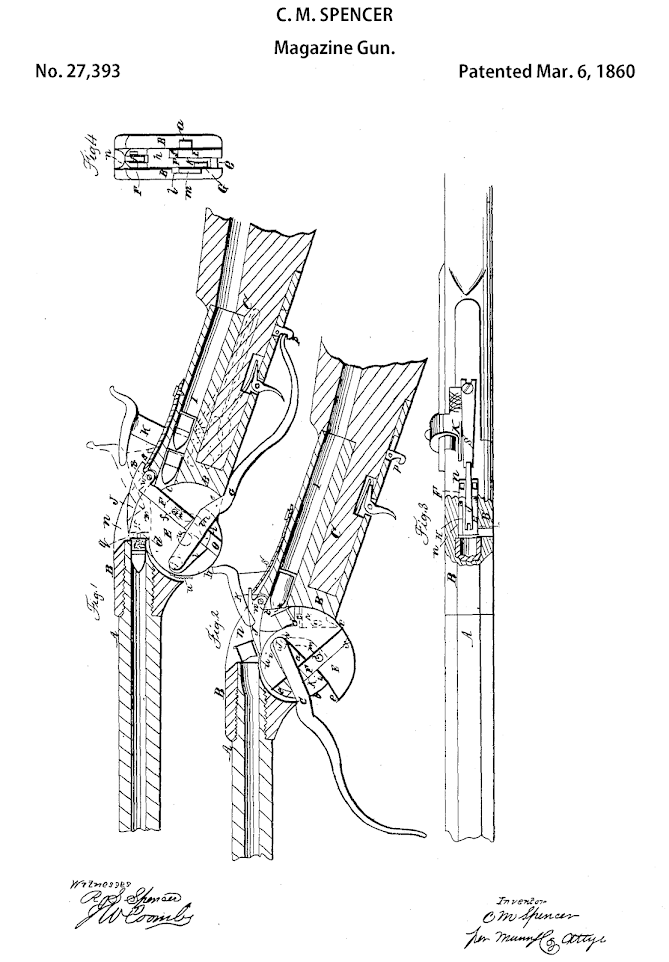

| Christopher Miner Spencer, Magazine Gun, U.S. patent number 27,393, March 6, 1860 |

At the time, a single-shot, muzzle-loaded gun could be fired perhaps three times a minute by an experienced rifleman. Spencer conceived of loading the weapon instead through the rifle breech (thus eliminating the need for ramming the round down the barrel), and created a magazine capable of storing seven shells, which could be sequentially spring-loaded and fired by simply cocking and replacing the trigger-guard lever. The “Spencer Repeating Rifle” was capable of firing 15 to 20 rounds a minute. Though his was not the first breech-loaded weapon, his improvements to the existing art justified a government patent, which he received in 1860.

|

| Christopher Miner Spencer |

Spencer’s company had early production and financing problems — he was, after all, an inventor and not a businessman — and was unable to meet even the modest Navy Department order in a timely fashion. But the real roadblock to wider military acceptance and development of the Spencer rifle was the Department of War Chief of Ordnance, Gen. James Ripley, who dismissed the Spencer and similar breechloaders as just “newfangled gimcracks,” and he refused to authorize their purchase.

After two years of personally demonstrating the Spencer to Army and Navy commanders in the field, including General Ulysses S. Grant (who reportedly pronounced it “the best breechloading arms available”), Spencer finally decided to take his case to the top. Again with Cheney’s aid, Spencer was able to secure a meeting with President Lincoln.

Security not being quite what it is today, Spencer recalled in his memoirs that:

on August 17, 1863, I arrived at the White House with the rifle in hand, and was immediately ushered into the executive room, where I found the President alone. After a brief introduction, I took the rifle from its cloth case and handed it to him. Examining it carefully, and handling it as one familiar with firearms, Mr. Lincoln requested me to take it apart ‘and show the inwardness of the thing.’ The separate parts were soon laid on the table before him. It was the simplicity of the gun which appealed to President Lincoln, and he was greatly impressed with the fact that all that was needed to take it apart was a screw driver. With this implement he bared the vitals of the gun and replaced them so that the gun was ready to shoot in a few minutes.

Impressed with its design, the president invited Spencer to meet him the next day to test the weapon himself.

Lincoln’s personal participation in the procurement process was not always supported by his appointees. Even Welles, one of the president’s fiercest and most loyal defenders, complained in his personal diary that the president was too involved in ordnance procurement. When Lincoln championed a new type of gunpowder to Dahlgren, Welles confided in his diary that he “cautioned [Dahlgren], as I have had occasion to do repeatedly, against encouraging the President in these well-intentioned but irregular proceedings. He assures me he does restrain the President as far as respect will permit, but his ‘restraints’ are impotent, valueless. He is no check on the President, who has a propensity to engage in matters of this kind and is liable to be constantly imposed upon by sharpers and adventurers. Finding the heads of Departments opposed to these schemes, the President goes often behind them, as in this instance; and subordinates, flattered by his notice, encourage him.”

True to form, Lincoln prepared to personally test the Spencer. At the appointed time on August 18, Spencer arrived at the White House and accompanied the president, his son Robert and an official from the Navy Department, who carried the rifle, target, and ammunition, for a short walk to the Mall, near the site of the unfinished Washington Monument. Lincoln stopped by the War Department on the way and his son Robert invited War Secretary Edwin M. Stanton to accompany the party for the test, but the secretary declined due to the press of business. “They do pretty much as they have a mind to over there,” mused the president philosophically. So, minus the hard-working secretary of war, the president’s party proceeded to the Mall to try out the Spencer Repeater.

This was not Lincoln’s only trip to the makeshift shooting range near the White House. One of his private secretaries, William O. Stoddard, recalled accompanying Lincoln on similar occasions: “On the grounds near the Potomac, south of the White House, was a huge pile of old lumber, not to be damaged by balls, and a good many mornings I have been out there with the President, by the previous appointment, to try such rifles as were sent in. There was no danger of hitting anyone, and the President, who was a very good shot, enjoyed the relaxation very much.” Another secretary, John Hay, reported that on these excursions Lincoln “used to quote with much merriment the solemn dictum of one rural inventor that ‘a gun ought not to rekyle; if it rekyled at all, it ought to rekyle a little forrid.’”

On this occasion though, the President was all business. Spencer recalled:

The target was a board about six inches wide and three feet high, with a black spot on each end, about forty yards away. The rifle contained seven cartridges. Mr. Lincoln’s first shot was about five inches low, but the next shot hit the bull’s-eye and the other five were close around it. ‘Now,’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘we will see the inventor try it.’ The board was reversed and I fired at the other bull’s-eye, beating the President a little. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘you are younger than I am and have a better eye and a steadier nerve.’

At the conclusion of the day’s shooting, Spencer was presented with the half of the target used by the president as a souvenir of his visit, which many years later he donated to the Lincoln Museum in Springfield, Illinois. The president meanwhile must have enjoyed the outing, and the uncommonly pleasant August weather, as he went out again the next day with his “Spencer” for another hour’s shooting with Hay.

|

| Inscription on Lincoln Target Board. 7 consecutive shots made by the President of the United States with Spencer at a distance of forty yards, Washington D.C. August 18, 1863. |

For Christopher Spencer and his fledgling company, the time spent at target practice with the president was well worth it. Less than a month after their meeting, the incorrigible and aging General Ripley was forcibly retired from active duty by Secretary Stanton, and assigned to be inspector of forts in New England. The Bureau of Ordnance soon after placed additional orders for the Spencer Repeaters, and by the end of the Civil War, some 85,000 of them (both rifles and carbines) had been put in service. (Rifle-like weapons with a barrel length of less than 20 inches are typically considered to be carbines. Weapons with barrels greater than 20 inches are usually called rifles unless specifically called carbines by the manufacturer.)

And only a month after Spencer’s outing with Lincoln, the Spencers proved their mettle. At the Battle of Chickamauga, a Union brigade under Col. John Wilder, all equipped with Spencers, held off and virtually destroyed a much larger Confederate regiment of Gen. John Bell Hood as it breached the Union lines and threatened to collapse the entire northern flank of the Union line’s southern branch.

The Spencer Repeater had only one stain on its record. In April 1865, less than two weeks after Lincoln’s assassination, Union soldiers searched for and surrounded a fugitive from justice in the Virginia countryside. As he lay dying in a barn on Garrett’s Farm, John Wilkes Booth was found armed with a large bowie knife, two pistols – and a Spencer carbine.

Jed Morrison, New York Times

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.