During the Civil War, Northerners organized sanitary fairs to raise funds on behalf of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), a charitable relief organization that promoted the welfare of Union Soldiers. The USSC was founded on June 9,1861 and deactivated in May of 1866.

President Lincoln institutes a centralized banking system to fund the Union in the Civil War in February of 1863. The USSC was a way to help subsidize the cost of the war.

|

| The Great Central Fair Buildings, Philadelphia, 1864. |

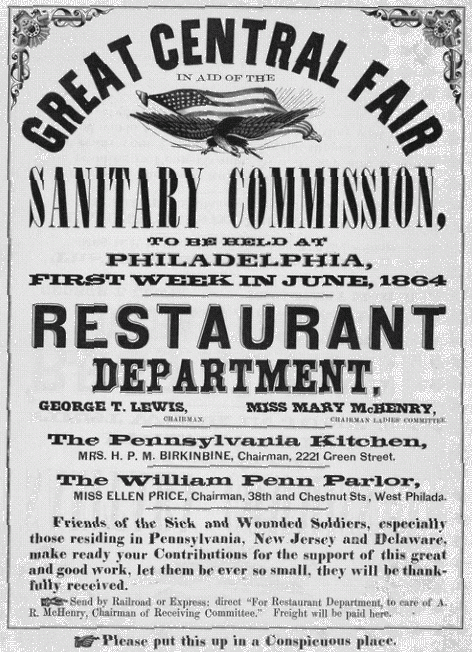

For three weeks in June 1864, the USSC held the Great Central Fair in Logan Square in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Several of these fairs had been held around the country and now it was Philadelphia’s time to prove their patriotism.

|

| Union Avenue Under Construction at the Great Central Sanitary Fair, Philadelphia, 1864. |

($250,000 today). It is phenomenal that the entire fair raised more than 1 million dollars ($16.573,000 today) during the third year of a devastating war.

On June 16, President Lincoln, his wife Mary, and a contingent of officials came from Washington D.C. to attend the event. The crowds crushed him as he attempted to walk down “Union Avenue," the main hall specially constructed for the event. Reports from fairgoers claimed he looked like he was enjoying himself although he didn't have the freedom to wander the fair like everyone else.

|

| Central Office of the USSC in Washington, D.C. |

Later that afternoon, Lincoln shared a light meal with a group of dignitaries and citizens. After the group toasted the President, he got up to address the crowd:

I suppose that this toast was intended to open the way for me to say something. [Laughter.] War, at the best, is terrible, and this war of ours, in its magnitude and in its duration, is one of the most terrible. It has deranged business, totally in many localities, and partially in all localities. It has destroyed property, and ruined homes; it has produced a national debt and taxation unprecedented, at least in this country. It has carried mourning to almost every home, until it can almost be said that the "heavens are hung in black.''

Although a self-educated man, Abraham Lincoln was well-read and was speaking to a well-educated audience. They would have caught that his comment, “heavens are hung in black,” was a reference to the opening lines of Shakespeare’s Henry VI, where the Duke of Bedford begins the play with a similar line, “hung be the heavens with black” mourning the death of the former King.

Lincoln, who enjoyed going to the theater, knew that a few productions of Shakespeare's plays hung black curtains on the back of the stage to represent that the production was a tragedy. The current war they were all experiencing, in “almost every home” was certainly such a tragedy.

Yet it continues, and several relieving coincidents [coincidences] have accompanied it from the very beginning, which have not been known, as I understood [understand], or have any knowledge of, in any former wars in the history of the world. The Sanitary Commission, with all its benevolent labors, the Christian commission, with all its Christian and benevolent labors, and the various places, arrangements, so to speak, and institutions, have contributed to the comfort and relief of the soldiers. You have two of these places in this city—the Cooper-Shop and Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloons. [Great applause and cheers.]

Lincoln’s speech was labeled as the “Speech at the Great Central Sanitary Fair.” To our 21st century ears, it sounds like a cleaning convention. But the USSC was a well-known volunteer group of citizens and businesses that presented ideas to General Winfield Scott, Head of the Army, beginning within weeks of the start of the war. Their purpose was “... to bring to bear the upon the health, comfort, and morale of our troops the fullest and ripest teachings of sanitary science in its application to military life.” The USSC, along with the Christian Commission, became involved in supplying medical, nutritional, spiritual, and sanitary assistance to the Union troops.

Locally, two establishments opened in Philadelphia within weeks of the beginning of the war to provide for the troops. The Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon was the largest of the two main providers, the other being the locally beloved Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon. Both establishments provided a bed, hot meals, opportunities to wash-up and bathe, and medical care for any soldier traveling through Philadelphia for individuals or for Regiments. Mr. Cooper eventually added a hospital on the second floor of his Saloon. Both establishments kept their doors open until the end of the war. Together they served well over a million men.

And lastly, these fairs, which, I believe, began only in last August, if I mistake not, in Chicago; then at Boston, at Cincinnati, Brooklyn, New York, at Baltimore, and those at present held at St. Louis, Pittsburg, and Philadelphia. The motive and object that lie at the bottom of all these are most worthy; for, say what you will, after all the most is due to the soldier, who takes his life in his hands and goes to fight the battles of his country. [Cheers.] In what is contributed to his comfort when he passes to and fro [from city to city], and in what is contributed to him when he is sick and wounded, in whatever shape it comes, whether from the fair and tender hand of woman, or from any other source, is much, very much; but, I think there is still that which has as much value to him [in the continual reminders he sees in the newspapers, that while he is absent he is yet remembered by the loved ones at home—he is not forgotten. [Cheers.]

A telling comment was made by a woman from New York, who was upset that her state did nothing for the traveling soldiers while “Philadelphia lets no regiment, of whatever State, whether going to or from battle, pass hungry through her streets.” Soldiers from other states also noted that “anyone who thinks there is any lack of support for the war has only to march through Philadelphia.”

Another view of these various institutions is worthy of consideration, I think; they are voluntary contributions, given freely, zealously, and earnestly, on top of all the disturbances of business, [of all the disorders,] the taxation and burdens that the war has imposed upon us, giving proof that the national resources are not at all exhausted, [cheers;] that the national spirit of patriotism is even [firmer and] stronger than at the commencement of the rebellion [war].

Next, Lincoln’s subject shifts to the war itself. Despite the patriotism of the Fair, the country was war-weary. The Presidential and federal elections were coming in the fall. Lincoln himself had just been re-nominated as a candidate of his party, although they were not calling themselves Republicans this time around, but rather National Unionists (1864–1865). His nomination had many detractors, and as poorly as the war was going, and how long it was dragging out, it did not look like he could win re-election. Lincoln took this opportunity to talk to this important electorate about the upcoming months:

It is a pertinent question often asked in the mind privately, and from one to the other, when is the war to end? Surely I feel as deep [great] an interest in this question as any other can, but I do not wish to name a day, or month, or a year when it is to end. I do not wish to run any risk of seeing the time come, without our being ready for the end, and for fear of disappointment, because the time had come and not the end. [We accepted this war; we did not begin it.] We accepted this war for an object, a worthy object, and the war will end when that object is attained. Under God, I hope it never will until that time. [Great cheering]

The political opponents of the President, the Democrats were willing to settle for peace immediately, even though it would probably mean either letting the South form their own country, or bring them back into the United States as slaveholding states. Neither was the object that the North went to war to fight for. The war had been extremely costly in lives and treasure, and Lincoln did not want to see that squandered in vain.

Speaking of the present campaign, General Grant is reported to have said, I am going through on this line if it takes all summer. [Cheers.] This war has taken three years; it was begun or accepted upon the line of restoring the national authority over the whole national domain, and for the American people, as far as my knowledge enables me to speak, I say we are going through on this line if it takes three years more. [Cheers.] My friends, I did not know but that I might be called upon to say a few words before I got away from here, but I did not know it was coming just here. [Laughter.] I have never been in the habit of making predictions in regard to the war, but I am almost tempted to make one. [(Do it---do it!)]---If I were to hazard it, it is this: That Grant is this evening, with General Meade and General Hancock, of Pennsylvania, and the brave officers and soldiers with him, in a position from whence he will never be dislodged until Richmond is taken [loud cheering],

Lincoln knew that the Battle for Petersburg, Virginia had started the day before. Generals Grant, Meade, and the popular Philadelphia born Hancock would hold down their position for almost nine months, in the trenches around Petersburg, before they finally captured Richmond in April 1865, just before the South surrendered.

and I have but one single proposition to put now, and, perhaps, I can best put it in form of an interrogative [interragatory]. If I shall discover that General Grant and the noble officers and men under him can be greatly facilitated in their work by a sudden pouring forward [forth] of men and assistance, will you give them to me? [Cries of "yes.''] Then, I say, stand ready, for I am watching for the chance. [Laughter and cheers.] I thank you, gentlemen.

Using his personal talent of involving the crowd, Lincoln wraps up with a hopeful look forward. He asks the audience for their help in “men and assistance” which probably had the multilayer meaning of not only their continued help raising money on the home-front, but possibly in raising the final troop counts to finish the war, and also their votes in the upcoming election. The crowd responded in the affirmative by cheers and verbal agreement.

President Lincoln finished the speech on a positive note with the encouraging voices of the citizens of Philadelphia wafting through the air on a beautiful and festive summer evening. One can only imagine this was a light-hearted celebratory event for the President, amongst so many other events where the war and politics were overwhelming in 1864.

The Great North-Western Sanitary Fair opens in Chicago, Illinois.

The last great Sanitary Fair of the war to raise funds for the United States Sanitary Commission and the Chicago, Illinois Civil War Soldier's Home located at 739 East 35th Street on May 30, 1865 and ran through June 24, 1865.

|

| The Great North-Western Sanitary Fair, Chicago, Illinois. |

The affair, with its centerpiece of Union Hall among the specially constructed buildings near the lakefront, raised more than $270,000 for sick and wounded soldiers. A highlight was the visit of General Grant and General Sherman.

Edited by Neil Gale, Ph.D.