|

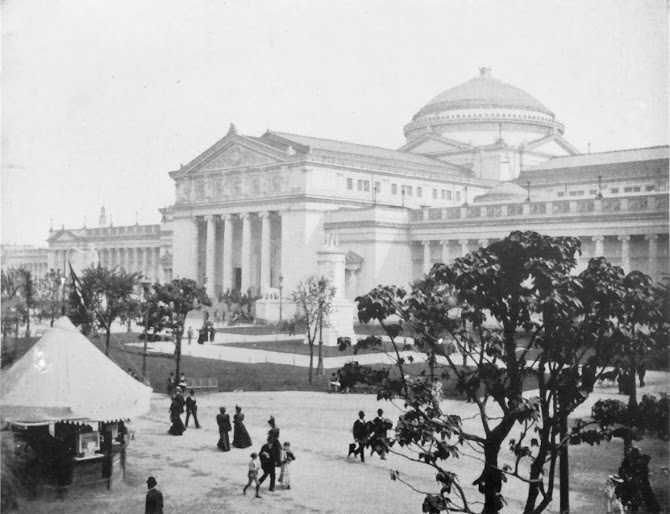

| The Palace of Fine Arts in 1893 - Today's Museum of Science and Industry. |

From the time the fair closed in 1893 until 1920, the Palace of Fine Arts building housed the Columbian Museum of Chicago.

In 1905, the name was changed to the Field Museum of Natural History to honor Marshall Field, the Museum's first major benefactor, and to emphasize its natural sciences collection in anthropology, botany, geology, and zoology.

Construction began in 1915 on a new home for the Field Museum of Natural History at its new site in Grant Park.

Specimens and collections were moved from the Jackson Park site to the Grant Park site in 1920.

In 1933, the Palace building re-opened as the Museum of Science and Industry in time for the Century of Progress World's Fair. The Museum of Science and Industry represents the only fire-proof and central building remaining from the World's Fair of 1893. The backside of the Museum (overlooking Jackson Park Lagoon) was actually the front of the palace during the Fair, and the color of the exterior was changed during renovations. But the building looks almost exactly the way it did in 1893. Some of the light posts from the fair still illuminate the museum campus.

On December 6, 1943, the Museum's name was changed to the Chicago Natural History Museum.

In the Post World War II Era, The Field Museum began a new exploration focusing on scientific research instead of collecting items for its exhibitions in 1945.

On March 1, 1966, trustees voted to change the Museum's name back to the Field Museum of Natural History.

WORLD'S CONGRESS BUILDING:

|

| World's Congress Building in 1893 - Today's Art Institute of Chicago |

The Interstate Industrial Exposition building, built in 1872, was razed in 1892 to construct the Art Institute. The construction contract was executed on February 6, 1892, and was officially opened to the public on December 8, 1893.

The World Congress Auxiliary of the World's Columbian Exposition occupied the new building from May 1 to October 31, 1893, after which the Art Institute took possession on November 1, 1893. The construction cost of the World's Congress Building was shared with the Art Institute of Chicago, which, as planned, moved into the building (the Museum's current home) after the Fair's close and officially opened to the public on December 8, 1893.

CLOW AND SONS SANITARY WATER CLOSET

1893 World's Columbian Exposition Water Closets (toilets) by the James B. Clow and Sons Sanitary Co. Tickets were sold for admission to the pay washrooms.

The paid washrooms had a sink and towels to wash your hands, and the free toilets did not have sinks. There were 3,000 Water Closets on the fairgrounds. This restroom building stands just behind the south side of the Museum of Science and Industry.

MAINE STATE BUILDING:

|

| 1893 Maine State Building as it Stands Today. |

THE DUTCH COCOA HOUSE:

|

| The Dutch Cocoa House |

THE PABST PAVILION:

Captain Frederick Pabst traveled from Milwaukee to the World's Columbian Exposition to display his brewery's products. After the fair closed, he moved his Pabst Pavilion, which had resided inside the enormous Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, to his recently completed Mansion in Milwaukee. The pavilion was attached to the east side of the home and used as a summer room. After Captain and Mrs. Pabst died in the early 1900s, the Pabst heirs donated the Mansion to the Catholic Archdiocese. Ironically, the Pabst Beer Pavilion was used as a private chapel for the Archbishop. In the 1970s, the Mansion was slated for demolition, and it was saved from the wrecking ball and is currently being restored as a period museum. The Pabst Pavilion serves as the museum gift shop. When you tour the Pabst Mansion Museum, you will likely enter through the Pabst Pavilion that was visited by World's Columbian Exposition Fair-goers 125 years ago.

|

| The Pabst Pavilion in 1893 |

A TICKET BOOTH FROM THE FAIR:

|

| A Ticket Booth From The 1893 World's Fair |

BUILDING OF NORWAY (aka THE NORWAY PAVILION):

|

| The Building of Norway at the 1893 World's Fair |

Tucked among some willow trees in the foreign building section in the northeast corner of the World's Columbian Exposition grounds stood a striking structure made of massive pine beams. Built in the style of a medieval stave church, its gabled roof with carved dragons evokes the prow of a Viking Ship.

The building officially opened on May 17 (Norwegian Constitution Day, "Syttende Mai"), but construction continued through June. During the Fair, the building served as an office and headquarters for the Norwegian Commission, offering only a few visitor displays. Some believe there was a chapel in the Norway Pavilion, but none existed.

When the Fair closed, the Norway Building was again taken apart and shipped by train to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and installed on the C. K. Billings summer estate. The Billings estate changed hands twice and was eventually owned by William Wrigley, Jr., who painted the Norway Building ochre yellow and used it as a home theatre.

In 1935, the family owners of the Norwegian-American Museum known as Little Norway negotiated the acquisition of the Norway Building. The building was dismantled one final time and shipped by truck to Blue Mounds, where it can be toured as part of the outdoor Little Norway Museum. One of the features that undoubtedly made the Norway Building more portable than most structures is that it is constructed without a single nail and is held together entirely by wooden pegs.

In 1935, the family owners of the Norwegian-American Museum known as Little Norway negotiated the acquisition of the Norway Building. The building was dismantled one final time and shipped by truck to Blue Mounds, where it can be toured as part of the outdoor Little Norway Museum. One of the features that undoubtedly made the Norway Building more portable than most structures is that it is constructed without a single nail and is held together entirely by wooden pegs.

BUILDING OF NORWAY UPDATE: September 19, 2015

Norway Building from the 1893 Chicago World's Fair heads home.

Olav Sigurd Kvaale walked up the old wooden stairs of the medieval-style church. He paused under the gabled portico and touched the intricate, 122-year-old carvings surrounding the massive door.

Olav Sigurd Kvaale walked up the old wooden stairs of the medieval-style church. He paused under the gabled portico and touched the intricate, 122-year-old carvings surrounding the massive door.

"This," he said, his hand on carvings, "is my grandfather."

A year earlier, Kvaale journeyed across the Atlantic from his home in Norway in a quest to learn more about his grandfather, Peder, a farmer and woodworker who, in the 1800s, was among a team of craftsmen in Norway who built the church, known as The Norway Building, for the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

Kvaale discovered a valuable gem of family history and a larger story of a building that had traveled on an extraordinary journey. Believed to be one of the last surviving structures from the Fair, it had been moved from Chicago to an estate in Lake Geneva — where, painted bright yellow, it served for a time as a private movie house for the Wrigley family — before ending up at a minor tourist attraction tucked into the rolling countryside 30 miles west of Madison.

By last year, the building was in danger of being lost. Water seeped through the wood-shingled roof, mice scurried along the floorboards, and rot chewed at the foundation.

When Kvaale first saw the building, though, he looked past the signs of disrepair and marveled at the artistry: the chiseled faces of Norse kings and queens, the dragon's tail that swirled around the exterior entranceway. This, he had learned from relatives, was his grandfather's proudest creative achievement. He vowed to try somehow to save it.

Now, after rallying support in the region of Norway where the building was initially constructed, Kvaale has returned to Wisconsin, this time with a team of a dozen Norwegian craftsmen. The clang of hammers and chisels echoes across the verdant valley. Piece by piece, windows, wall panels, and support beams are painstakingly removed, labeled, and laid out on the surrounding lawn.

The Norway Building is going home.

A winding road cuts through the forest, leading to the now-shuttered tourist attraction, Little Norway.

Operated by the same family since 1937, the quaint attraction had, over the years, drawing thousands of visitors, who came to walk in the gardens, peek into the small Museum of Norwegian artifacts, or take a tour led by guides in traditional Norwegian dress.

The half-dozen original log cabin buildings on the property had been erected in the mid-1800s by a Norwegian immigrant farmer, who built them, according to Norwegian tradition, on a south-facing slope to catch the sun's warmth. Each building had been meticulously restored and furnished with Norwegian antiques and artwork.

The most striking feature of the property was, no doubt, the Norway Building, which stood on the hillside overlooking the valley. With its gabled roof topped by dragons and ornate shingles crafted to look like reptilian scales, the building gave the secluded property a sense of enchantment and made a visit feel like stepping into the pages of a fairy tale.

Commissioned by Norwegian officials for the World's Fair, it had been built as a symbol of cultural pride. It is patterned after the stave churches that, in the Middle Ages, dotted the rugged Norwegian landscape.

After the Fair, The Norway Building was moved to Lake Geneva, where it was installed on a lakeside estate eventually owned by the Wrigleys. A wealthy Norwegian-American named Isak Dahle acquired it in 1935 and brought it to his summer retreat in Blue Mounds.

Almost as soon as Dahle had erected the ornate building on his rural property, neighbors began hopping a fence to come to see it. So Dahle hired a caretaker and charged admission, 5¢ for adults and 3¢ for children.

In the era before Disneyland, people flocked to see the spectacle in the Wisconsin woods. It even attracted Norwegian royalty. Crown Prince Olav, who later became king of Norway, came for a tour in 1939, and his son, Crown Prince Harald, the current king, visited in 1965, according to the 1992 book "The Norway Building of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair."

Over the years, Dahle's descendants continued to run Little Norway, which was open from May to October. But attendance declined as the world became more modern and entertainment options proliferated.

"We didn't have interactive things or movies or anything like that. Part of the goal at Little Norway was to stay the same," said Scott Winner, 55, a grand-nephew of Dahle who returned from college in 1982 thinking he'd help out for the summer but fell in love with the place and decided to stay. "It was like the place that time forgot."

The Winner lived in a large stone house his grandparents had built. He raised his two children there and considered his work at Little Norway as "a labor of love." He said he rarely did more than break even and often lost money.

His wife worked in business development for the Wisconsin Department of Commerce. For years they kept Little Norway afloat by selling the lumber from their surrounding 270-acre property. But rising insurance costs and taxes, Winner said, along with sparse attendance, forced them in 2012 to close the doors.

Every day for two years, Winner would look out his kitchen window at The Norway Building and wonder what would become of it. Several historical foundations explored a possible purchase, and negotiations with one continued for over a year but eventually collapsed.

The future seemed bleak in the summer of 2014 when Winner began receiving phone messages from a man in Norway who said he wanted to visit.

For weeks, Winner ignored the man's calls. He wanted to save time with tourists, and he needed to find a buyer, or The Norway Building would undoubtedly fall into ruin.

Four thousand miles away, in Norway, Olav Sigurd Kvaale was plumbing his family's history.

As a Christmas gift, an uncle had given him a photo of The Norway Building, and a notation at the photo's edge explained that Kvaale's grandfather had worked on the building's carvings.

Kvaale Googled the Norway Building and immediately found the website for Little Norway. Excited to see his grandfather's handiwork, he arranged to travel to Wisconsin with a group of relatives.

After he booked the plane tickets, he learned that Little Norway had been shuttered.

He called the phone number on the Little Norway website, but no one answered. He emailed a local reporter who had written about the attraction in hopes of getting contact information for the owner but had yet to be successful. He even tried the local Rotary Club.

Finally, a distant relative of Kvaale's in Seattle reached Winner by phone and convinced him of the importance of the visit. A date was set.

In the following weeks, Kvaale and his relatives worried about what they would find in Wisconsin. The Norway Building had, by then, endured three moves over its 120 years.

They were emotionally overcome when they arrived at Little Norway on a crisp, clear afternoon in September 2014. Kvaale's cousin, Sigrid Stenset, wept to see the carvings around the entranceway. They recognized the patterns as ones their grandfather later repeated in furniture and cabinetry, two of which sat in Kvaale's living room in Norway. They were confident their grandfather's hands had crafted the intricate designs.

And inside, they were pleasantly surprised at the building's condition.

Driving away, Kvaale and his relatives began to hatch a plan.

Back in Norway, Kvaale organized a coalition of friends and began to approach donors and politicians. He wrote about the building's plight for the local historical society, and a newspaper picked up the tale.

Stave churches are points of national pride in Norway. Built with wooden posts — "stave" in Norwegian — and featuring Viking motifs, they date to the Middle Ages. Britannica.com says there were once as many as 800 to 1,200, but only about 30 survive. Today they draw tourists from around the world.

Although The Norway Building is technically a replica of a stave church, Kvaale and his allies felt confident that, if it were returned to Norway, it would attract visitors and thus boost the local economy. The building's vagabond history, they believed, told a unique story.

With the effort gaining momentum, a Norwegian government official contacted Winner in October. "He said, 'Would you be willing to sell it?'" Winner recalled. "I said, 'If it returns to its home, I think it would be a romantic idea. '"

A delegation from Norway came to inspect the building in April and, impressed with how well it had held up, decided it was strong enough to move. They agreed to pay the Winners $100,000, with the local Norwegian government and private donors kicking in an estimated $600,000 for dismantling and shipping. Their goal is to have the building restored, rebuilt, and open to the public by next summer in Orkdal, where it was born.

"There are, of course, people (in Norway) who think this money should be spent another way," said Kai Roger Magnetun, the cultural director of Orkdal. "But I feel certain that when the building arrives in Orkdal, almost everyone will be proud."

The M. Thames & Co. factory, once located in the city of Orkanger, is gone, but many residents in the area are descendants of those who once worked there. Locals will be interested in the preservation, Magnetun said, and many are already following the disassembly on a Facebook page and a website, ProjectHeimatt.org, which means "going home."

The sale has been bittersweet for Scott Winner, whose family has cared for The Norway Building for three generations. On a Sunday not long ago, he climbed the hillside before dawn, sat on the building steps and sobbed.

He and his wife, Jennifer, first kissed on those steps. They were married inside, beneath the St. Andrew's crosses. His parents were married there too.

But watching the Norwegians work over the last two weeks had provided reassurance.

"They're taking such great caretaking it down. They want to save all these little trim pieces," he said. "They really are saving it."

On a recent day, scaffolding hugged The Norway Building, which had been stripped of roof sections, several walls, and many of its ornaments. Once displayed, spewing fire from the gables, the huge carved dragons lay prone in the grass.

As Kvaale pulls up shingles and floorboards, he likes to think about his grandfather.

"I want my grandfather to know we are taking this building back to Norway," Kvaale said. "I like to think that maybe he looks down on us."

The project is not only about moving a building, he said, but also about honoring his ancestor's work. His grandfather and many others constructed the building over just three months in 1893. They had worked with such careful craftsmanship that the building has survived a long, meandering journey across two continents.

"This is the last move," Kvaale said. "When it comes to Orkdal, it must stand there and stay there."

It will, he said, finally be home.

THE NORWAY BUILDING IS NOW IN ORKDAL, NORWAY.

CONCLUSION:

Since many other buildings at the fair were intended to be temporary, they were removed after the Fair. Their facades were made not of stone but of a mixture of plaster, cement, and jute fiber called staff, painted white, giving the buildings their "gleam." Architecture critics derided the structures as "decorated sheds." The White City, however, so impressed everyone who saw it (at least before air pollution began to darken the facades) that plans were considered to refinish the exteriors in marble or some other material.

On the afternoon of Monday, July 10, 1893, four Chicago firemen, eight firemen hired by the Columbian Exposition, and three civilians lost their lives in a fiery inferno that leveled the cold storage building. It was the greatest loss of life in the Chicago Fire Department up to that point.

In any case, these plans were abandoned in July 1894 when much of the fairgrounds was destroyed in a fire (rumored to have been started by squatters), thus assuring their temporary status.

ADDITIONAL READING:

BUILDING OF NORWAY UPDATE: September 19, 2015

Norway Building from the 1893 Chicago World's Fair heads home.

"This," he said, his hand on carvings, "is my grandfather."

A year earlier, Kvaale journeyed across the Atlantic from his home in Norway in a quest to learn more about his grandfather, Peder, a farmer and woodworker who, in the 1800s, was among a team of craftsmen in Norway who built the church, known as The Norway Building, for the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

Kvaale discovered a valuable gem of family history and a larger story of a building that had traveled on an extraordinary journey. Believed to be one of the last surviving structures from the Fair, it had been moved from Chicago to an estate in Lake Geneva — where, painted bright yellow, it served for a time as a private movie house for the Wrigley family — before ending up at a minor tourist attraction tucked into the rolling countryside 30 miles west of Madison.

By last year, the building was in danger of being lost. Water seeped through the wood-shingled roof, mice scurried along the floorboards, and rot chewed at the foundation.

When Kvaale first saw the building, though, he looked past the signs of disrepair and marveled at the artistry: the chiseled faces of Norse kings and queens, the dragon's tail that swirled around the exterior entranceway. This, he had learned from relatives, was his grandfather's proudest creative achievement. He vowed to try somehow to save it.

Now, after rallying support in the region of Norway where the building was initially constructed, Kvaale has returned to Wisconsin, this time with a team of a dozen Norwegian craftsmen. The clang of hammers and chisels echoes across the verdant valley. Piece by piece, windows, wall panels, and support beams are painstakingly removed, labeled, and laid out on the surrounding lawn.

The Norway Building is going home.

A winding road cuts through the forest, leading to the now-shuttered tourist attraction, Little Norway.

Operated by the same family since 1937, the quaint attraction had, over the years, drawing thousands of visitors, who came to walk in the gardens, peek into the small Museum of Norwegian artifacts, or take a tour led by guides in traditional Norwegian dress.

The half-dozen original log cabin buildings on the property had been erected in the mid-1800s by a Norwegian immigrant farmer, who built them, according to Norwegian tradition, on a south-facing slope to catch the sun's warmth. Each building had been meticulously restored and furnished with Norwegian antiques and artwork.

The most striking feature of the property was, no doubt, the Norway Building, which stood on the hillside overlooking the valley. With its gabled roof topped by dragons and ornate shingles crafted to look like reptilian scales, the building gave the secluded property a sense of enchantment and made a visit feel like stepping into the pages of a fairy tale.

Commissioned by Norwegian officials for the World's Fair, it had been built as a symbol of cultural pride. It is patterned after the stave churches that, in the Middle Ages, dotted the rugged Norwegian landscape.

After the Fair, The Norway Building was moved to Lake Geneva, where it was installed on a lakeside estate eventually owned by the Wrigleys. A wealthy Norwegian-American named Isak Dahle acquired it in 1935 and brought it to his summer retreat in Blue Mounds.

Almost as soon as Dahle had erected the ornate building on his rural property, neighbors began hopping a fence to come to see it. So Dahle hired a caretaker and charged admission, 5¢ for adults and 3¢ for children.

In the era before Disneyland, people flocked to see the spectacle in the Wisconsin woods. It even attracted Norwegian royalty. Crown Prince Olav, who later became king of Norway, came for a tour in 1939, and his son, Crown Prince Harald, the current king, visited in 1965, according to the 1992 book "The Norway Building of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair."

Over the years, Dahle's descendants continued to run Little Norway, which was open from May to October. But attendance declined as the world became more modern and entertainment options proliferated.

"We didn't have interactive things or movies or anything like that. Part of the goal at Little Norway was to stay the same," said Scott Winner, 55, a grand-nephew of Dahle who returned from college in 1982 thinking he'd help out for the summer but fell in love with the place and decided to stay. "It was like the place that time forgot."

The Winner lived in a large stone house his grandparents had built. He raised his two children there and considered his work at Little Norway as "a labor of love." He said he rarely did more than break even and often lost money.

His wife worked in business development for the Wisconsin Department of Commerce. For years they kept Little Norway afloat by selling the lumber from their surrounding 270-acre property. But rising insurance costs and taxes, Winner said, along with sparse attendance, forced them in 2012 to close the doors.

Every day for two years, Winner would look out his kitchen window at The Norway Building and wonder what would become of it. Several historical foundations explored a possible purchase, and negotiations with one continued for over a year but eventually collapsed.

The future seemed bleak in the summer of 2014 when Winner began receiving phone messages from a man in Norway who said he wanted to visit.

For weeks, Winner ignored the man's calls. He wanted to save time with tourists, and he needed to find a buyer, or The Norway Building would undoubtedly fall into ruin.

Four thousand miles away, in Norway, Olav Sigurd Kvaale was plumbing his family's history.

As a Christmas gift, an uncle had given him a photo of The Norway Building, and a notation at the photo's edge explained that Kvaale's grandfather had worked on the building's carvings.

Kvaale Googled the Norway Building and immediately found the website for Little Norway. Excited to see his grandfather's handiwork, he arranged to travel to Wisconsin with a group of relatives.

After he booked the plane tickets, he learned that Little Norway had been shuttered.

He called the phone number on the Little Norway website, but no one answered. He emailed a local reporter who had written about the attraction in hopes of getting contact information for the owner but had yet to be successful. He even tried the local Rotary Club.

Finally, a distant relative of Kvaale's in Seattle reached Winner by phone and convinced him of the importance of the visit. A date was set.

In the following weeks, Kvaale and his relatives worried about what they would find in Wisconsin. The Norway Building had, by then, endured three moves over its 120 years.

They were emotionally overcome when they arrived at Little Norway on a crisp, clear afternoon in September 2014. Kvaale's cousin, Sigrid Stenset, wept to see the carvings around the entranceway. They recognized the patterns as ones their grandfather later repeated in furniture and cabinetry, two of which sat in Kvaale's living room in Norway. They were confident their grandfather's hands had crafted the intricate designs.

And inside, they were pleasantly surprised at the building's condition.

Driving away, Kvaale and his relatives began to hatch a plan.

Back in Norway, Kvaale organized a coalition of friends and began to approach donors and politicians. He wrote about the building's plight for the local historical society, and a newspaper picked up the tale.

Stave churches are points of national pride in Norway. Built with wooden posts — "stave" in Norwegian — and featuring Viking motifs, they date to the Middle Ages. Britannica.com says there were once as many as 800 to 1,200, but only about 30 survive. Today they draw tourists from around the world.

Although The Norway Building is technically a replica of a stave church, Kvaale and his allies felt confident that, if it were returned to Norway, it would attract visitors and thus boost the local economy. The building's vagabond history, they believed, told a unique story.

With the effort gaining momentum, a Norwegian government official contacted Winner in October. "He said, 'Would you be willing to sell it?'" Winner recalled. "I said, 'If it returns to its home, I think it would be a romantic idea. '"

A delegation from Norway came to inspect the building in April and, impressed with how well it had held up, decided it was strong enough to move. They agreed to pay the Winners $100,000, with the local Norwegian government and private donors kicking in an estimated $600,000 for dismantling and shipping. Their goal is to have the building restored, rebuilt, and open to the public by next summer in Orkdal, where it was born.

"There are, of course, people (in Norway) who think this money should be spent another way," said Kai Roger Magnetun, the cultural director of Orkdal. "But I feel certain that when the building arrives in Orkdal, almost everyone will be proud."

The M. Thames & Co. factory, once located in the city of Orkanger, is gone, but many residents in the area are descendants of those who once worked there. Locals will be interested in the preservation, Magnetun said, and many are already following the disassembly on a Facebook page and a website, ProjectHeimatt.org, which means "going home."

The sale has been bittersweet for Scott Winner, whose family has cared for The Norway Building for three generations. On a Sunday not long ago, he climbed the hillside before dawn, sat on the building steps and sobbed.

He and his wife, Jennifer, first kissed on those steps. They were married inside, beneath the St. Andrew's crosses. His parents were married there too.

But watching the Norwegians work over the last two weeks had provided reassurance.

"They're taking such great caretaking it down. They want to save all these little trim pieces," he said. "They really are saving it."

On a recent day, scaffolding hugged The Norway Building, which had been stripped of roof sections, several walls, and many of its ornaments. Once displayed, spewing fire from the gables, the huge carved dragons lay prone in the grass.

As Kvaale pulls up shingles and floorboards, he likes to think about his grandfather.

"I want my grandfather to know we are taking this building back to Norway," Kvaale said. "I like to think that maybe he looks down on us."

The project is not only about moving a building, he said, but also about honoring his ancestor's work. His grandfather and many others constructed the building over just three months in 1893. They had worked with such careful craftsmanship that the building has survived a long, meandering journey across two continents.

"This is the last move," Kvaale said. "When it comes to Orkdal, it must stand there and stay there."

It will, he said, finally be home.

Decedents of the Norwegian workers who originally constructed the building brought a team of skilled craftsmen to Wisconsin in 2015 to disassemble the structure again for a trip back to Norway. With $600,000 in funds and more than 10,000 hours of labor by a team of volunteers, the structure was restored and reassembled. September 9, 2017, a dedication ceremony welcomed the structure, renamed the Thams Pavillion, to its new home in Orkdal, Norway.

CONCLUSION:

Since many other buildings at the fair were intended to be temporary, they were removed after the Fair. Their facades were made not of stone but of a mixture of plaster, cement, and jute fiber called staff, painted white, giving the buildings their "gleam." Architecture critics derided the structures as "decorated sheds." The White City, however, so impressed everyone who saw it (at least before air pollution began to darken the facades) that plans were considered to refinish the exteriors in marble or some other material.

On the afternoon of Monday, July 10, 1893, four Chicago firemen, eight firemen hired by the Columbian Exposition, and three civilians lost their lives in a fiery inferno that leveled the cold storage building. It was the greatest loss of life in the Chicago Fire Department up to that point.

In any case, these plans were abandoned in July 1894 when much of the fairgrounds was destroyed in a fire (rumored to have been started by squatters), thus assuring their temporary status.

ADDITIONAL READING: