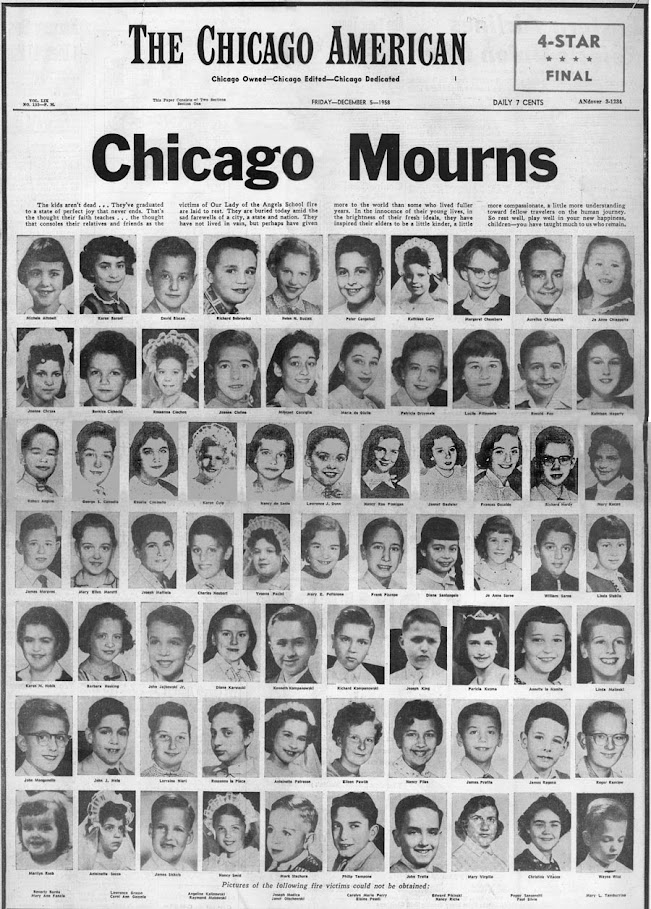

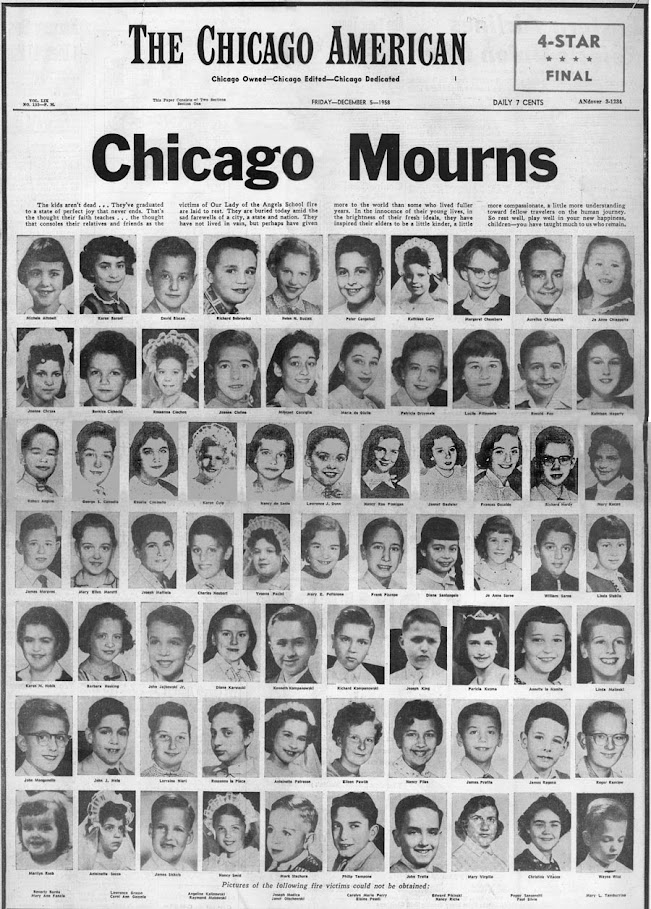

The fire at Our Lady of the Angels School, 909 North Avers Avenue in Humboldt Park, Chicago, snatched the lives of 87 children and 3 nuns on December 1, 1958, and then claimed 5 more children who later died from their injuries.

Founded in 1894, Our Lady of the Angels Church and School had once been predominantly Irish. Still, by 1958, the church, school, and neighborhood had transformed into a mixture of working-class immigrant families from Eastern and Northern Europe – especially Italy. Less than a decade after the fire, many parishioners of Our Lady of the Angels in the West Humboldt Park neighborhood, once one of Chicago's largest parishes, moved away from the neighborhood full of haunting memories.

Several months after the fire, the Chicago Archdiocese razed the remains of the old school building and built a new steel school building in operation by 1960.

Our Lady of the Angels School closed in 1999 and was eventually renovated and transformed into a charter school. Our Lady of the Angels parish merged with St. Francis Assisi Parish in 1991, and the Archdiocese rented the church, which was undamaged by the fire, to the New Miracle Temple Church of God in Christ for 20 years. Over time, Francis Cardinal George hoped to renovate the church.

Transforming the Remnants of Tragedy

Fifty-plus years after the 1958 fire at Our Lady of the Angels Catholic School, work on the once forlorn and neglected church next door is completed, and the church again presents a proud and hopeful face to a shabby neighborhood. Our Lady of the Angels Church, the scene of such tragedy, is now known as the Mission of Our Lady of the Angels. Father Bob Lombardo, the pastor of the Mission, remembered the church as a "handyman's special" when he arrived in 2006. He called the transformation of Our Lady of the Angels a miracle because estimates of the cost of its renovation reached nearly two million dollars. The actual cost was minimal because of volunteer labor and donated supplies.

On Saturday, April 15, 2012, an emotional crowd of about 400 people commemorated the reopening of Our Lady of the Angels. Francis Cardinal George dedicated the Mission of Our Lady of the Angels, and the Chicago Archdiocese decided that the renovated church would function as a neighborhood outreach and prayer center, offering occasional Masses. The Mission plans to expand its current "Feed the Needy" program, which already serves about 700 West Side families.

Many people in the crowd were survivors of the Our Lady of the Angels fire, and many were former parishioners. The memory of that cold, clear first Monday in December 1958 remained as vivid to them as sunlight glinting off Lake Michigan.

Just an Ordinary School Day in an Ordinary Chicago Parochial School

Our Lady of the Angels parish, with more than 4,500 families, was one of the largest parishes in the Chicago Roman Catholic Archdiocese during the 1950s. Our Lady of the Angels Church, an adjacent rectory, a convent of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the school was the neighborhood's central hub.

Our Lady of the Angels School provided education for pupils from kindergarten through eighth grade for over 1,600 students. Over 1,400 second through eighth-graders attended classes in the main school building at 909 North Avers Avenue at the intersection of West Iowa Street and North Avers Avenue in the Humboldt Park section of Chicago's west side. More than 200 kindergarten and first-grade students went to classes in two annexes on the Our Lady of the Angels campus on Hamlin Avenue.

Built in 1910, the school's two-story north wing had been remodeled several times, and in 1939, the entire building became a school when a newer church opened. By 1951, an annex connected the north wing to a south wing dating from 1939. The two original buildings and the annex formed a -U-, with a narrow fenced courtyard separating them. The school had a brick exterior, and its interior consisted of wooden stairs, walls, floors, doors, twelve-foot acoustical tiled ceilings, and a wooden roof. The school's second-floor windows were 25 feet above the ground, and its English-style basement extended partially above ground level.

Each classroom door had a glass transom above it, providing ventilation and a pathway for flames and smoke to enter the room. The school had one fire escape, no automatic fire alarms, and no direct fire alarm connection to the fire department. It had no fire-resistant stairwells and no heavy-duty fire doors from the stairwells to the second-floor corridor. There were two unmarked fire alarm switches in the school, both in the south wing. The four fire extinguishers in the north wing were mounted seven feet off the floor, unreachable for many adults and virtually all children. The school didn't have a fire alarm box on the sidewalk outside.

Although Our Lady of the Angels was generally clean and well maintained, it mirrored some potentially fatal flaws of 1950s schools and municipal and state fire regulations. Pupils hung their coats on hooks in the hallway or in cloakrooms instead of in metal lockers, and there was no limit to the number of children in a classroom. Sometimes, as many as 60 students crowded a classroom built to hold half or one-quarter of that number.

Our Lady of the Angels school legally met the 1958 municipal and state requirements and had passed a routine fire department safety inspection a few weeks before December 1, 1958. A grandfather clause in the 1949 state fire safety codes said that older schools like Our Lady of the Angels were not required to install safety devices that the code required in schools built after 1949. Our Lady of Angels was a fire waiting to be ignited by modern standards, and it ignited on December 1, 1958.

In 1958, the ethnic makeup of Chicago's Our Lady of the Angels was predominantly Italian-American, with a smaller but significant presence of Polish-American members. The parish had experienced a demographic shift in the decades leading up to the fire, transitioning from a predominantly Irish-American community to one with a larger Italian-American population. This shift was reflective of broader trends in Chicago's neighborhoods as Italian Americans migrated to the city from the early 20th century onwards.

While the exact percentages of each ethnic group within the parish are difficult to determine definitively, estimates suggest that Italian Americans likely comprised around 70-80% of the membership, with Polish Americans accounting for the remaining 20-30%. There were also a small number of Mexican-American families who belonged to the parish.

A Fire Flares and Flourishes

At 2:35 PM Central Standard Time on December 1, 1958, many Our Lady of the Angels School pupils concluded their lessons. In Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng's seventh-grade history class in Room 208, Andrea Gagliardo, 12, concentrated on "The Missionaries in Florida and Louisiana." In Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne's fifth-grade geography class in Room 212, John Mele, 10, wrote a question in his notebook: "Where along the Atlantic Coastal Plain can oysters be found?" In room 209, Michele McBride, 13, waited with her eighth-grade classmates for the closing bell to ring at 3 o'clock, less than half an hour away.

While students upstairs waited to be dismissed, a fire smoldered in a cardboard trash barrel at the foot of the northeast stairwell in the basement of the older north wing of Our Lady of the Angels School. For about thirty minutes, the fire burned undiscovered, and it heated the stairwell and filled it with light grey smoke that eventually turned thick and black. At about 2:25 PM, three eighth-grade girls, Janet Delaria, Frances J. Guzaldo, and Karen Hobik, were returning from an errand.

When the girls reached Room 211, their second-floor classroom in the north wing, they encountered thick smoke. They promptly told their teacher, Sister Helaine O'Neill, who jumped up from her desk and lined up her students to evacuate the building. Moments later, she opened the classroom door to the hallway, but she decided that the dense smoke made it too dangerous to escape down the stairs leading to Avers Avenue on the building's west side. She and her students sat in their classroom, waiting to be rescued.

Two other events occurred approximately the same time Sister Helaine O'Neill and her students waited for rescue. Intense heat shattered a window at the foot of the staircase, feeding the fire and serving as a chimney, sending hot gases, fire, and black smoke pouring up the stairs to the second floor.

As he walked by the building, the school janitor, James Raymond, saw a red glow through a window and raced into the basement furnace room. He saw a fire through a door leading into the stairwell. He warned two boys emptying trash baskets in the boiler room to leave, and then at approximately 2:30 PM, he rushed to the rectory and told the housekeeper to call the fire department. Then he raced back to the school to help students to escape down the fire escape. The boys ran back to their classroom and warned their lay teacher, and after unsuccessfully searching for the school principal, she and another lay teacher led their students out of the school building.

The lay teacher pulled the fire alarm as she left the school building, but it didn't ring. She left her students safely in the church, returned to the school, and successfully activated the fire alarm. The fire alarm rang inside the school, but since the notice was not automatically connected, it did not summon the fire department.

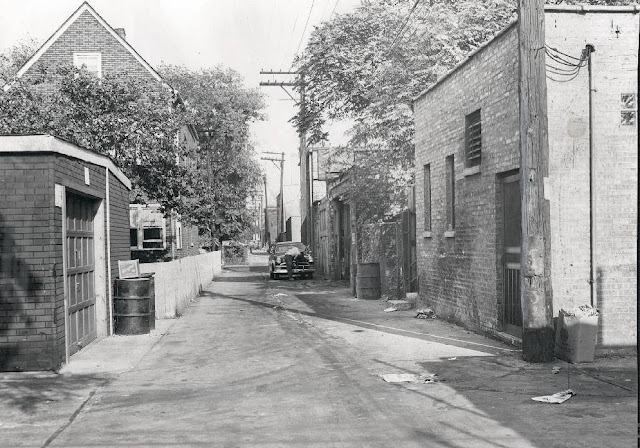

The first telephone call from the rectory reached the fire department at 2:42 PM. A second call came in from Barbara Glowacki, the candy store owner in the alley along the north wing of Our Lady of the Angels.

The Fire Stalked Them, but Brave Rescuers Saved Many

By the time the fire department arrived, the fire had spread rapidly for about forty minutes. The Chicago Fire Department initially fought an uphill battle to control the fire at Our Lady of the Angels School. The housekeeper calling in the fire alarm had given the rectory address on West Iowa Street instead of the school address, making it necessary to reposition fire trucks and hose lines.

Firemen rose to the challenge, called additional firefighting equipment and immediately began to rescue the pupils still in the burning school. Still, the teachers and students on the second floor of the north wing were trapped. The firemen had to back a fire truck into a seven-foot iron picket fence to get ladders to the windows on the north wing. Five teaching nuns and 239 children had two terrible choices. They could either jump from their second-floor windows to land on the concrete and crushed rock 25 feet below them or wait for the fire department to rescue them.

Some nuns urged the children to sit at their desks, form a semicircle, and pray. In-room 209, Sister Mary Davidis Devine ordered her 55 students to pile books and furniture in front of the classroom doors, which helped slow the invasion of smoke and flames until rescuers came. Eight Room 209 students escaped with injuries, and two died.

|

Firefighter Richard Scheidt carrying

John Michael Jajkowski, Jr. from the school. |

Michelle McBride from Room 209 burned over 60 percent of her body, and she spent four and a half months in the hospital, enduring numerous operations. The operations continued for years after the fire, as did the constant pain from her injuries. In 1979, Michele McBride wrote a book, The Fire That Will Not Die, about her Room 209 experience, the only firsthand account of that day. Her sister reported that Michele died on July 4, 2001, from chronic physical problems from the fire.

Sam Tortorice, the father of another student from 209, Rose Tortorice, ran into the school, climbed onto an awning below Room 209's rear window, and began to help students escape. Father Joseph Ognibenewho, who happened to be driving by the school, joined him, and as a team, they helped students flee through the window and into a window in the annex. From there, they hurried down the only metal staircase in the school and escaped through the main entrance on Iowa Street.

Neighbors of Our Lady of Angels ran home and brought ladders to the alley on the north side of the school, hoping to rescue students through classroom windows. Mario Camerini, a part-time assistant janitor at the school, had the only ladder tall enough to reach the windows of Room 208. The tall ladder and the men operating it allowed approximately 25 children to escape room 208. Twelve students and their teacher, Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng, died in room 208.

Andrea Gagliardo, the 12-year-old –girl in Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng's seventh-grade history class in Room 208 who had been studying "The Missionaries in Florida and Louisiana," climbed out on a ledge, and firemen eventually rescued her. Andrea remembered that "some of the boys jumped out of the window. When we looked down, we saw them lying still on the ground. It was like a miracle when we saw the firemen with their ladders."

The 57 children in room 210, located on the north side of the second floor in the center of the north wing overlooking the alley north of the school, were fourth-graders, younger and smaller than the children in the other five north wing second-floor classrooms. People placed several ladders below the windows of Room 210 before the fire department arrived, but the ladders were too short. Many children hung from the window ledge and dropped onto a ladder or directly to the ground.

When they finally reached Room 210, the firemen found many dead fourth-graders wrapped around Sister Mary Seraphica Kelley for protection. Although 29 students managed to escape, 28 students and Sister Kelley died in Room 210, more students than in any other classroom.

Room 212 housed Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne's fifth-grade class of 55 students. The fire didn't invade Room 212 as quickly and burned less intensely because of its location in the northwest corner of the north wing, the second floor of the school, which could account for the fact that 29 pupils survived in this room. The smoke and toxic fire gases were as deadly here as in the other school rooms, and most of the 26 pupils who died here were smothered before the fire department could rescue them. Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne also died.

John Raymond, the son of James Raymond, the school janitor, jumped from a window and survived. He recalled, "Although we did not have a fire in our class, the heat and smoke were unbearable. Sister did all she could to buy us time, but it was not. She gave her life trying to save kids right to the end."

John Mele, 10, the boy from Room 212 who wondered, "Where along the Atlantic Coastal Plain can cans of oysters be found?" did not survive to discover the answer to his question.

As the fire progressed, thick black smoke and superheated air turned second-floor classrooms into infernos. Children crawled and fought their way to the windows, and many with their hair and clothes on fire jumped, fell, or were pushed out of windows before the firemen and ladders could reach them. The fall killed some of the children and seriously injured others. Many smaller children couldn't climb over the high window stills or were pushed aside by other children desperately trying to escape. Firemen struggled to rescue students and nuns as the fire flashed over classrooms filled with screaming children. Most of the school's roof collapsed, and the superheated downdraft likely killed anyone left on the second floor.

Panicked parents raced to Our Lady of the Angels from all over the city, and the police soon had to set up barriers to restrain the anxious crowd of about 5,000 parents and onlookers. The group grew as the afternoon wore on, and firefighters carried a blanket and sack-covered bodies from the school.

The December Day That 92 Pupils and Three Nuns Didn't Return from School

By early evening, fire departments from all over Chicago had the five-alarm fire under control, and firemen had rescued more than 160 children from their burning school. They carried others out already dead, some with badly charred bodies. Injured children were taken to local hospitals, and the deceased to the Cook County Morgue basement and to a police station where officials had set up a makeshift station to identify the dead children.

A United Press International story reported when the firemen extinguished the fire at Our Lady of the Angels about six o'clock that evening, the second floor was blackened entirely, and people could look through the second floor from one end to the other, with just a wall in the middle to obstruct their view. Ladders leaned against the burned-out school on three sides, hoses and safety nets covered the ground, and discarded children's clothing and school books scattered about, poignant reminders of the tragedy. News of the fire spread across and stunned Chicago and, eventually, the entire country.

Three Nuns and 92 Children

Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne, Sister Mary Seraphica Kelley, and Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng died protecting and consoling their pupils at Our Lady of the Angels school. They were not identified by name in many newspaper stories or at their funeral mass. Before the 1960s, few professional women had a public presence -many were invisible and silent. Catholic women in the traditional patriarchal church knew and accepted this as a fact of life.

In his sermon during the funeral mass for the three nuns on December 4, 1958, Monsignor William E. McManus referred to the three nuns as "professional women and experienced teachers." He praised them for their "gallant heroism," but he didn't name them because he believed that they "would want to be remembered simply as the Blessed Virgin Mary Sisters who died with their pupils in the fire."

In her article "Stunned with Sorrow, " Suellen Hoy," in the summer of 2004, Chicago History Magazine, pieces together the lives of Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne, Sister Mary Seraphica Kelley, and Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng. She resurrects them from the mists of time and history and reveals them as vibrant people and teachers. She gives them a presence and a voice.

A comprehensive website called Our Lady of the Angels features stories of the children who survived and did not survive and their pictures. The site reconstructs the details of the fire and its aftermath and has links to newspaper stories of the day about the tragedy.

The Fire is Gone, but its Impact Lives On

In 1962, a boy who had been a ten-year-old fifth-grader at Our Lady of the Angels at the time of the fire confessed to setting the fire. On the day of the fire, his teacher had excused him to go to the boy's restroom at 2:00 PM when the fire had begun smoldering in the bin at the foot of the stairs. A fire investigator later found burned matches in the sacristy area of the basement chapel of the north wing of the school. Although the boy had a history of setting fires and told details about the fire that he should not have known, he recanted his confession. He was never prosecuted. Officially, the cause of the fire is unknown.

|

| Officials inspect Sister M. Clare Therese Champagne's classroom after the 1958 fire at Our Lady of the Angels School. |

In 1959, the National Fire Protection Association issued a report about the Our Lady of the Angels fire, blaming civic authorities and the Archdiocese of Chicago for, in its words, allowing "fire traps such as Our Lady of the Angels School to be legally operated despite having inadequate fire safety standards." The report also noted that the open stairways, delayed discovery, alarms, and lack of automatic fire protection in the building were the same time-worn reasons for fires.

A coroner's jury recommended wiring all schools to the city fire alarm box, enclosing open stairwells, and installing automatic sprinklers.

sidebar

Some critics have alleged that the Archdiocese attempted to "sweep the fire under the rug" in order to avoid negative publicity and protect its reputation. They point to several factors that they believe support this claim.

- The Archdiocese initially blamed the fire on faulty wiring, despite evidence that suggested otherwise. Investigators later determined that the fire was likely caused by an overheated fan in the school's basement.

- The Archdiocese resisted calls for a public inquiry into the fire. The Archdiocese argued that such an inquiry would be unnecessary and would only serve to relive the pain of the families who had lost loved ones.

- The Archdiocese settled lawsuits with the families of the victims out of court. This decision prevented the release of potentially damaging information about the Archdiocese's role in the fire.

The Archdiocese has denied that it attempted to cover up the fire or its aftermath. The Archdiocese has said that it did everything it could to help the families of the victims and to prevent future tragedies.

In the six decades since the Our Lady of the Angels fire, many safe new schools have been built, and fire fighting and fire prevention technology have made tremendous strides. But old-school buildings still have open stairwells, insufficient fire alarms, and no automatic sprinkler system.

|

| A monument to the victims of Our Lady of the Angels School in the Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois. |

FILM FOOTAGE

Chicago Fire Department:

Our Lady Of Angels School Fire

Francis Cardinal George and Hope for the Future

Francis Cardinal George told the congregation at the Mission of Our Lady of the Angels dedication ceremony that he hoped the renewed building would be a beacon of peace that could give a new start to a struggling neighborhood. He praised the groups contributing to the rapid renovation of the church, saying, "I was so pleased and grateful that they all dared to come out and be together in this way, and that's the best sign of hope."

Lots of mistakes were made by lots of individuals. This includes building codes, historic safety exceptions, the fact that fire engines couldn't get close enough, and second-floor windows were out of range of the fire department's highest ladders. Even standard floor wax and wooden school infrastructure led to igniting and spreading the fire. Meanwhile, one nun saved her entire class with quick thinking.

By Kevin Sinnott, whose father served on a commission that studied the fire and response.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Contributor Kathy Warnes