The crisis forced the city's engineers and aldermen to take the drainage problem seriously, and after many heated discussions — and following at least one false start — a solution eventually materialized. In 1856, engineer Ellis S. Chesbrough drafted a plan to install a city-wide sewerage system and submitted it to the Common Council, which adopted the project.

Workers then laid drains, covered and refinished roads and sidewalks with several feet of soil, and raised most buildings to the new grade with hydraulic jacks.

|

| The Briggs House, corner Randolph Street and Fifth Avenue (today Wells Street). |

The work was funded by private property owners and public funds.

The first masonry building in Chicago was raised in January 1858. It was a four-story, 70-foot long, 750-ton brick structure situated at the northeast corner of Randolph and Dearborn Streets. It was lifted on two hundred jackscrews to its new grade, 6 feet 2 inches higher than before, "without the slightest injury to the building." This was the first of more than fifty similar-sized buildings raised that year.

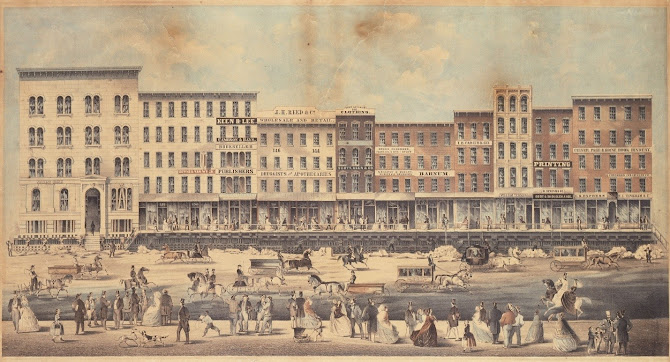

By 1860, confidence was sufficiently high that a consortium of no fewer than six engineers, James Brown, James Hollingsworth, and George Pullman. They took on one of the most unique locations in the city and hoisted it entirely up to grade in one go. They lifted half a city block on Lake Street, between Clark Street and LaSalle Street, a solid masonry row of shops, offices, printer shops, etc., 320 feet long, comprising of 4 and 5-story brick and stone buildings. The footprint took up almost one acre. The estimated all-in weight, including sidewalks, was 35,000 tons.

In five days, the entire assembly was elevated 4 feet 8 inches in the air by a team of 600 men using 6,000 jackscrews. The next step is to build a new foundation. The spectacle drew crowds of thousands, and people were permitted to walk under the lifted buildings among the jackscrews on the final day.

The following year a team led by Ely, Smith, and Pullman raised the Tremont House hotel on the southeast corner of Lake Street and Dearborn Street. This building was luxuriously appointed, was of brick construction, was six stories high, and had a footprint of over 1 acre. Once again, business as usual was maintained as this vast hotel parted from the ground it was standing on. Indeed some of the guests staying there at the time, among whose number were several VIPs and a US Senator, were utterly oblivious to the feat as the five hundred men operating their five thousand jackscrews worked under covered trenches.

|

| The street level looks like it was raised by about 8 feet. |

Another notable feat was raising the Robbins Building, an iron building 150 feet long, 80 feet wide, and five stories high, located at the corner of South Water Street and Wells Street. This was a big building; its ornate iron frame, twelve-inch thick masonry wall-filling, and "floors filled with heavy goods" made for a weight estimated at 27,000 tons, a large load to raise over a relatively small area. Hollingsworth and Coughlin took the contract and, in November 1865, lifted not only the building but also the 230 feet of stone sidewalk outside it. The total mass of iron and masonry was raised 27.5 inches, "without the slightest crack or damage.

Many of central Chicago's hurriedly erected wooden frame buildings were now considered wholly inappropriate to the burgeoning and increasingly wealthy city. Rather than raise them several feet, proprietors often preferred to relocate these old frame buildings, replacing them with new masonry blocks built to the latest grade. Consequently, the practice of putting the old multi-story, intact and furnished wooden buildings, sometimes entire rows of them all at the same time — on rollers and moving them to the outskirts of town or to the suburbs was so common as to be considered nothing more than routine traffic.

|

| Raised this house to new street level. |

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.