|

| White City's land before construction began. |

|

| Advertising sign for White City Construction Company. |

|

| The "Scene Palace" is under construction, and a roller coaster is in the background. 1904 |

White City even had an answer to the Eiffel Tower, a giant "Electric Tower" that could be seen from 15 miles away. It was a beacon to the masses, a shining sign that the happiness brought by that 1893 fair could still be found. There was a giant Ferris wheel, too.

“I'm glad of one thing, boys... we will give the people of Chicago an opportunity to enjoy themselves as they have never dreamed of. When I think of the hot, stuffy theatres in Chicago on summer evenings, when I think of the absolute barrenness of the lives of so many thousands of men, women, and children there who have no place to go for clean, unobjectionable entertainment and pleasure, I'm glad that we are going to build White City, from humanitarian principles if for no other reason.”

White City introduced the world to the Goodyear Blimp, first assembled at the park.

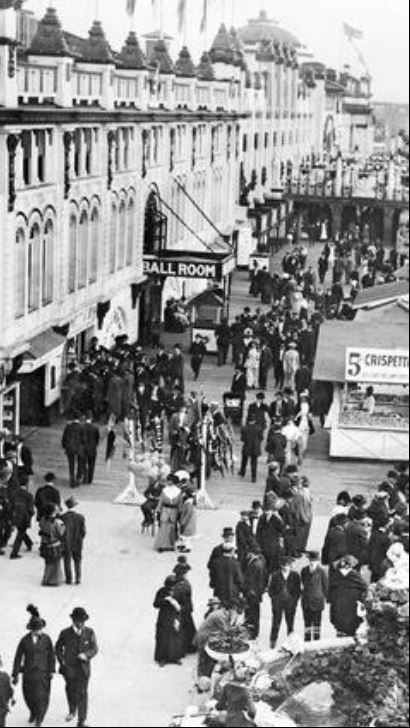

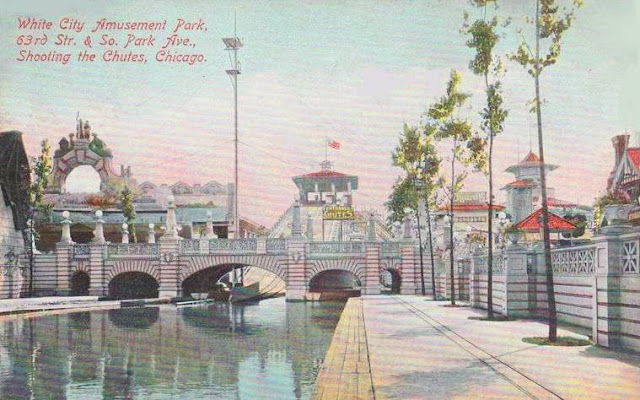

Among the many attractions, White City offered a Ballroom (featuring the "All-Star White City Orchestra"), a Casino, a Chinese Theatre, a White City Roller rink, a Bowling Alley, a penny arcade, a "Pep" Roller Coaster, Giant Racing Coaster; the Flash; Shoot the Chutes; the Canals of Venice (a pretty water ride); Water Scooters; Dodgem; Lindy Loop; Seaplane; Giant Ferris wheel; The Whip; a Miniature Railroad; and the House of a Thousand and One Trouble (funhouse); Illusion Show; Freak Show; Midget City; Mechanical City; Hug House (funhouse); Fire & Flame exhibition; Baseball Park and Athletic Field; Picnic grounds; and A beer garden. White City included a spacious outdoor theatre.

There was a special section of the park devoted to kiddie rides.

Similar action to the "Lindy Loop" ride.

The Mysterious Sensation (a funhouse), in particular, is one of the greatest novelties in the history of White City. It was likened to Riverview's Aladdin's Castle and a Haunted House mixed together. It was billed as one of the most unique entertainment features ever exhibited anywhere.

There was free parking for 1000 motorcars. White City had various concession stands around the park. One could pick out almost anything they want in the line of novelties, useful articles, and even edibles. The concessions sold silk umbrellas, floor lamps, aluminum-ware, silverware, dolls, candy, bags, overnight cases, clocks, vases, glassware, and other items too numerous to classify.

While the park did offer a happy diversion for many, it was for whites only – even as the neighborhood surrounding the park became increasingly populated by African Americans as a result of the Great Migration.

However, the great depression and the ongoing problems from the fires of 1925 and 1927 negatively impacted White City. Although 1930 still wasn't too bad for White City, with each successive year, attendance declined, and by 1933, the company that operated it was unable to pay the taxes that were due, causing the park to be placed in receivership and forced to close in 1933.

|

| Bird's Eye View of White City. 1905 |

THE WHITE CITY ROLLER RINK

The same anti-black policies that had beset the amusement park also applied to the roller rink at the park. The rink was still open, and in the 1940s, it became the site of demonstrations and brawls as Blacks fought for their right to roller skate indoors.

The same anti-black policies that had beset the amusement park also applied to the roller rink at the park. The rink was still open, and in the 1940s, it became the site of demonstrations and brawls as Blacks fought for their right to roller skate indoors. In 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was involved in one of these rallies.

In 1946, the Congress of Racial Equality sued the management of the rink, saying it was violating the Illinois Civil Rights Law. Eventually, the White City roller rink (which was named White because of the million electric light bulbs) closed in 1949. The roller Rink changed its name to Park City and was desegregated. However, the Park City rink closed in 1958.

In the 1950s, the 694-unit Parkway Gardens housing project was built on the site.

White City Amusement Park Attractions

1905 detailed descriptions with photographs and illustrations in PDF.

- Automatic Vaudeville

- Ballroom

- Beautiful Venice

- Boats and Gondolas

- Bumps, A New and Novel Pastime

- Camp of Gypsies

- Chinese Theatre

- College Inn Restaurant

- Cummins' Wild West Indian Congress

- Double Whirl Ride

- Electric Theatre [Moving Pictures]

- Fire Department

- Fire Show

- Flying Airships

- Fun Factory

- Gum Chewers [Zeno Gum Vending Machines]

- Hereafter

- Infant Incubators

- Johnstown Flood

- Merry-Go-Round

- Miniature Railroad

- Observation Wheel

- Over and Under the Sea

- Photograph Gallery [White City Photo Company]

- Puzzle Garden

- Scenic Railway

- Shooting the Chutes

- Simian City [aka: The Dog, Pony and Monkey Circus or The Animal Circus]

- Temple of Music

- The Midway

- Toboggan [aka: Figure 8 & Double Circle]

- White City's Hospital

1905 WHITE CITY ADVERTISEMENTS

|

| White City Opening Day Advertisements |